- cross-posted to:

- history@hexbear.net

- cross-posted to:

- history@hexbear.net

Pictured: Bodies from the massacre at Menelik Square. Courtesy of Ian Campbell’s The Addis Ababa Massacre: Italy’s National Shame.

Recently a user by the name of @Dolores@hexbear.net expressed a desire to see a thread on Fascist Italy’s atrocities, because too many of us treat Fascist Italy as nothing more than a joke.

While it is undeniable that all of the Axis powers made very costly mistakes, and that laughing at our enemies can be therapeutic, we still risk underestimating them if we focus solely on their weaknesses. Moreover, the atrocities that the Italian Fascists committed should be neither overlooked nor forgotten. The following is an incomplete overview of those atrocities.

Preinstitutional Fascism

Pictured: Squadristas, a Fascist paramilitary (similar to the Freikorps).

The Fascists were massacring thousands of people even before the March on Rome in the October of 1922. Quoting Micheal Clodfelter’s Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, page 330:

Benito Mussolini, a former socialist, founded the ultra‐right Fasci di Combattimento (Union of Combat) in 1919. Funded by rich landowners and businessmen, the Blackshirts, many of whom were former officers and soldiers, engaged the Italian left in a series of bloody riots in the nation’s streets and fields, which resulted in the deaths of 300 fascists and 3,000 leftists between October 1920 and October 1922.

Details of these conflicts can be learnt from A. Rossi’s The Rise of Italian Fascism, 1918–1922. An example from pages 121–2:

In this connection Mario Cavallari, a war volunteer, tells of the following events which took place in the province of Ferrara at the end of March 1921: ‘The fascists are accompanied on their expeditions by lorries full of police, who join in singing the fascist songs. At Portomaggiore, an expedition of more than a thousand fascists terrorized the country with night attacks, fires, bomb‐throwing, invasion of houses, massacre under the eyes of the police.

Further, as fast as the lorries arrived they were stopped by the police, who blocked every entry, and asked the fascists if they were armed, doling out arms and ammunition to those who were not. Houses were searched and arrests made by fascists, and for two days a combined picket of fascists and police searched all those who arrived at the Pontelagoscuro station, allowing only fascists to enter the country.’

Gaetano Salvemini’s Under the Axe of Fascism, page 18:

At the end of 1920 the Fascists began methodically to smash the trade unions and the co‐operative societies by beating, banishing, or killing their leaders and destroying their property. They made no distinction between Christian‐Democrats and Socialists, […] between Socialists and Communists, or between Communists and Anarchists. All the organisations of the working classes, whatever their banner, were marked out for destruction because they were “Bolshevist.”

Formerly restricted to colonies like British India and the Belgian Congo, the Fascists (probably coincidentally) introduced in Europe the treatment of punishing opponents by forcing them to ingest excessive quantities of castor oil, thereby inducing diarrhea and potentially causing death. Quoting Hamish Macdonald’s Mussolini and Italian Fascism, pages 15 & 17:

Gabriele D’Annunzio […] demonstrated a new style of government, in which the economy would be run by ten corporations, which would elect the upper house of Parliament. Many of his ideas — including the setting up of a private army (militia), the use of the Roman salute, parades, speeches from balconies, the war cry, ‘Eia, eia, alalà’, and forcing opponents to swallow castor oil—were later adopted by the Fascist movement set up by Benito Mussolini.

[…]

Commanded by local Fascist leaders known as ras (an Abyssinian/Ethiopian word for chieftain), the action squads sacked and burnt down the offices and newspaper printing shops of the Socialist Party, trades unions and Catholic peasant leagues. Typically, they beat up opponents with clubs (called manganelli; singular manganello). They humiliated their victims by forcing them to drink castor oil or swallow live toads; or left them naked and tied up to trees, some distance from their homes.

Both the German Fascists and Spanish fascists adopted the castor oil treatment (and possibly the others).

Frequently unmentioned is that the early Fascists were hostile towards Slavs, especially Croats and Slovenes. (This may be surprising given Fascist Italy’s later alliance with the so‐called ‘Independent State of Croatia’.) Much like the German Fascists equated Jews with Bolsheviks, and the Japanese Imperialists equated the Hainanese with communists, the early Italian Fascists equated (Southern) Slavs with socialists. Slavs in Trieste suffered as a result of Fascism. From Maura Hametz’s The carabinieri stood by: The Italian state and the “slavic threat” in Trieste, 1919–1922:

The presence of Slovene and Croatian minorities and the re‐emergence of a strong, well‐organized, and vocal socialist party in Trieste after the First World War fueled Italian fears of the threat of the “Slavic menace” equated in this instance with the “red contagion.”

[…]

In both the Fascist‐inspired attack against the Slovene cultural center Narodni Dom and the destruction of the Croatian‐managed Adriatic Bank in July 1920, state troops likely abetted nationalist aggression. Despite orders to defend against attacks on minorities, the carabinieri failed to act to disperse mobs until after the institutions were destroyed.40 Although the Triestine press and public opinion condemned the violence perpetrated against the Slavs in July 1920, it had proceeded with the protection of, or at least under the noses of, soldiers stationed in the nearby barracks.41

Institutional Fascism

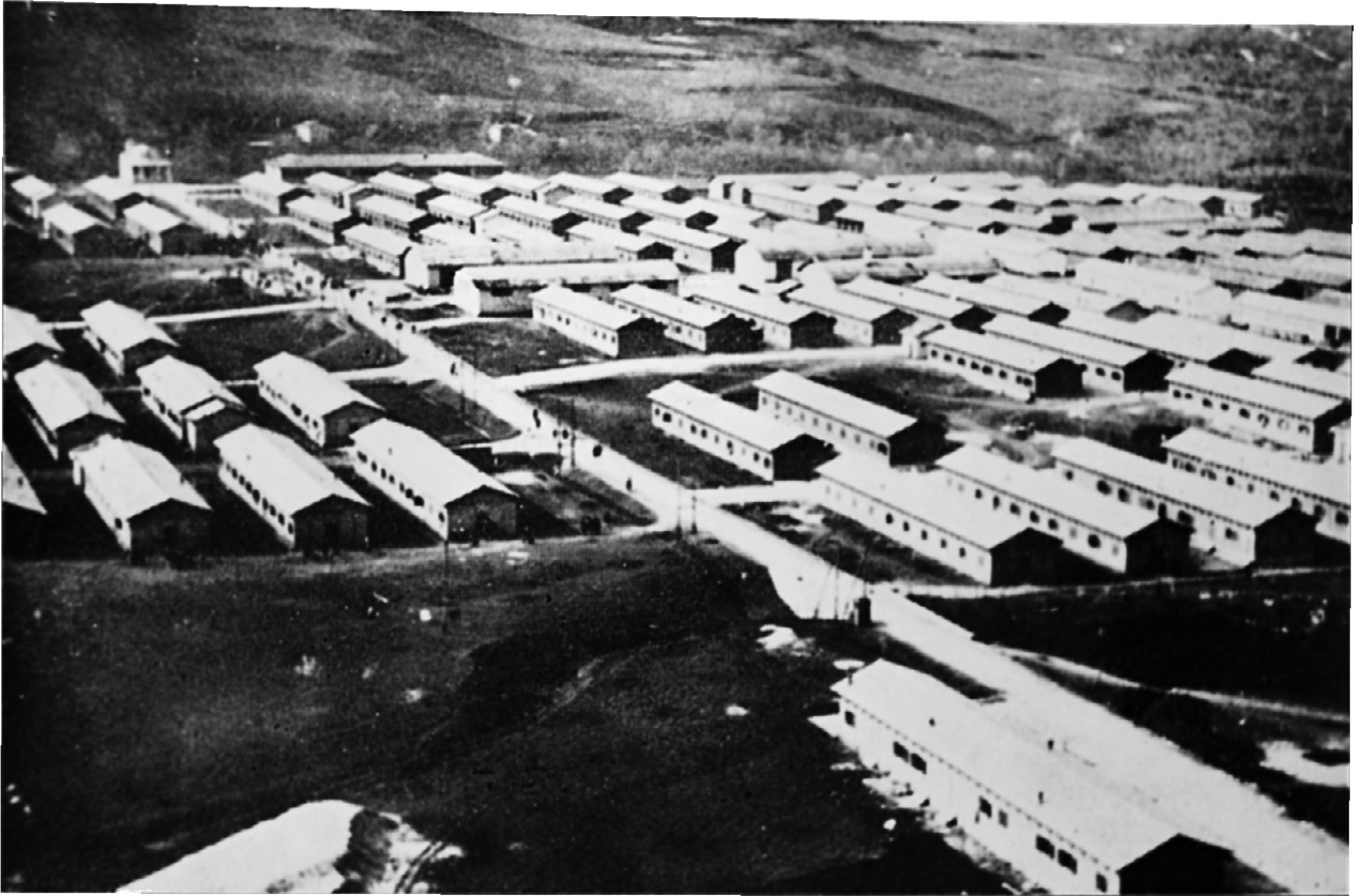

Pictured: Concentration camp of Fraschette (Latium), 1943. Courtesy of Carlo Spartaco Capogreco’s Mussolini’s Camps: Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940–1943).

It is difficult to find estimates on how many Italian civilians the Fascists killed. We know that Fascist Italy killed political opponents at least occasionally, most famously Giacomo Matteotti, but finding numbers or even amounts is uneasy. On the other hand, Capogreco’s Mussolini’s Camps: Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940–1943) indicates how many political prisoners Fascist Italy held. Pages 20–1:

Most sentences delivered by the provincial boards pertaining to confinement centered on political motives.79 However, [F]ascist Italy never enacted the mass deportation campaigns of political opponents that took place in [the Third Reich] during 1933–1934. At the end of 1926, confined dissidents numbered 900. From 1926 to 1943, throughout the 17 years when the laws about confinement applied, it reached the total of 12,330.80

These figures show Italy to have a much lower level than the internal political deportation figures reached by [the Third Reich]. In fairness, one should add to these figures those pertaining to the opponents subjected to civilian internment, an activity that, as we will see, Fascism used liberally for political repression.81

[…]

[Italian] Fascism did not have to enact mass deportations because, in 1926, there were no threats of insurrection in Italy. During the first half of the 1920s, political dissent had already been defeated, even with bloodshed, by fascist squadrismo, and tens of thousands of dissidents had already taken shelter abroad.86 Repression was limited, therefore, to selecting the most visible dissidents, and isolating them through political confinement.87

The relatively few remaining political dissidents were not the only ones who had much to fear from the Fascist state. A number of gay men (even some who served Fascism) were surveilled, deported, or in some other way harassed by Fascist officials. Roma and Sinti were likewise unspared. Indeed, many ordinary citizens were at risk for detention; the red scare was alive and well in Fascist Italy. Page 13:

The risk of deportation did not pertain only to active anti‐fascists or broad opponents of the régime. People could be condemned for a long list of specious accusations, often based solely on hearsay, and activities,11 including preaching.12

As Emilio Lussu wrote, “the school professor, the defense lawyer, the writer of novels, the idle café‐goer, the laborer who criticized a decrease in salary,” and other citizens, could become, without knowing it, political deportees.13

Indeed, confinement even served as deterrent to control the less engaged opponents of the régime or the generic “grumblers,” as well as fascists believed to be guilty of dissidence.14 This alienating reality was certainly harder on women, who found themselves dealing with confinement from a position of isolation that was much deeper than the one experienced by the men.15

Even the conquest of the Empire became a good opportunity to fatten the lists of those sent to confinement, as new imperial subjects were gradually added to its numbers.16

The point on women is worth emphasizing; when the lower classes rose up against Fascism in the mid‐1940s, the Fascist bourgeoisie would torment and massacre many antifascists, some of whom were women. Quoting Victoria de Grazia’s How Fascism Ruled Women, page 274:

Forty‐six hundred women were arrested, tortured, and tried, 2,750 were deported to [Axis] concentration camps, and 623 were executed or killed in battle. Working‐class and peasant women, most of whom were close to the communist resistance, made up the majority.

Similarly to the ‘clean Wehrmacht’ myth, there is also a ‘clean Regio Esercito’ myth, although when scholars discuss this subject they usually call it the (Italiani,) brava gente or ‘good Italian’ myth, which is a broader category that makes no distinction between the armed and unarmed. Nevertheless, a great deal of brava gente involves exonerating the army, which, contrary to popular belief, was not staffed with incompetent buffoons. I’ll be referring to them frequently throughout the rest of this post.

Fascism in Spain

Pictured: Units from the Corpo Truppe Volontarie.

Quoting Javier Rodrigo’s Fascist Italy in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939:

The [Fascist Italy’s] intervention was vital for the [Spanish fascists’] victory. The sending of troops and supplies and the fascist armed forces’ open participation in the conquest of territory, the bombing of military and civilian targets, and the naval war had a significant impact in determining the main features of the Civil War, from both a Spanish and an Italian perspective.

[…]

The bombing of the towns of Durango and Elorrio on 31 March by Savoia‐Marchetti aircraft of the [Fascist] air fleet, escorted by Fiat CR‐32 fighters, caused some 250 victims, most of them civilians. It also heralded the beginnings of a bombing technique which the [Fascist] squadrons would use for the duration of the war: repeated flyovers and sometimes at high altitude in order to evade the anti‐aircraft defences, and, above all, air attacks with no declared military objectives other than the principal military objective of terrorising the population.

[…]

The Catalan government, the Generalitat, used a bomb fragment to try and prove [Fascist] involvement in a bombing raid. The attack had impressed the ‘French’ by its severity, which was apparently what mattered the most to Ciano.64 It was not the only one in Catalonia. [Fascist] bombs also fell on Reus, Badalona, and Tarragona, striking the city’s historic centre, causing numerous civilian victims, and the fuel tanks, which were practically destroyed in September.

[…]

Nor was there any rejection of violence by the military administrators of the 155th Battalion of Workers, formed in Miranda del Ebro from 400 Republican prisoners allocated to serve the CTV [Corpo Truppe Volontarie], whose leaders imposed punishments contrary to the codes of military justice by tethering prisoners’ feet and hands to trees or lampposts and ‘by keeping them there for several days’, as one of them, the head of the concentration camp at San Juan de Mozariffar, complained.

Nor, of course, was there any rejection of violence by those in charge of the Frecce Nere in which Dario Ferri fought. According to him, they decided on the summary shooting of four civil guards for firing at them from the castle of Girona when they occupied the city.129

Fascism in Africa

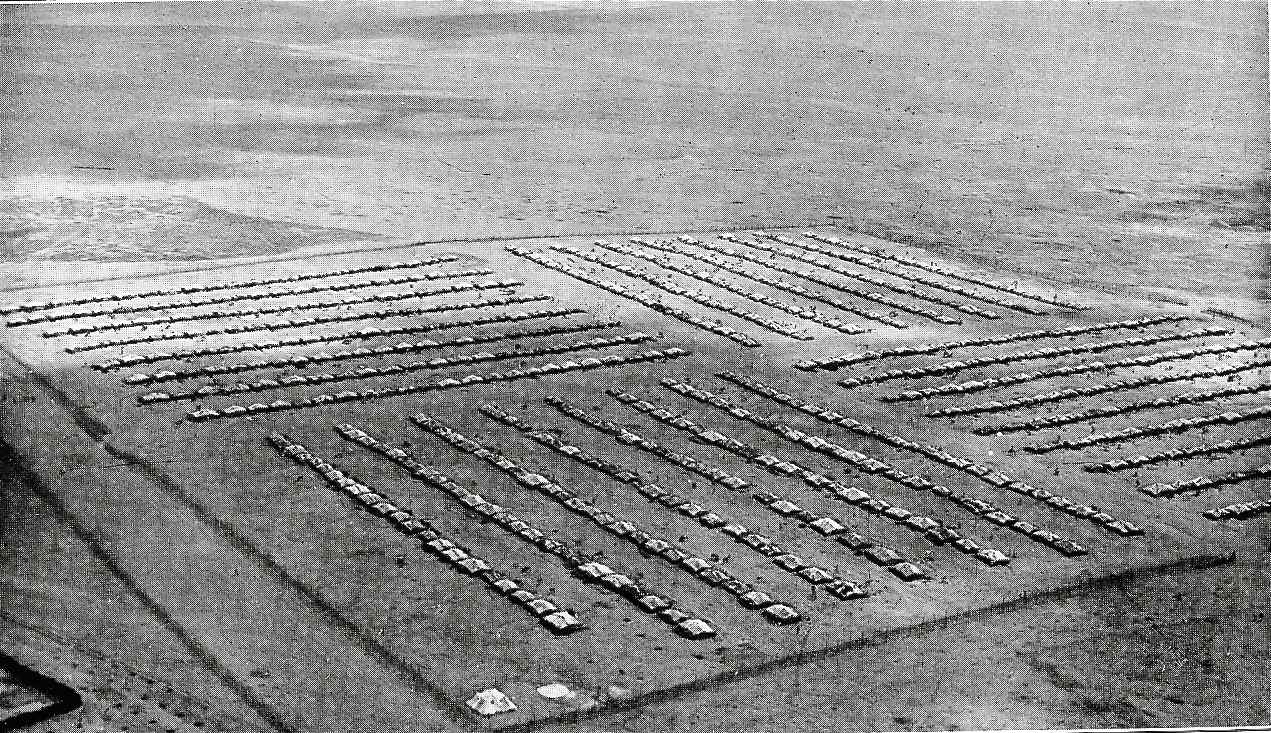

Pictured: Fascist concentration camp in Libya.

The Fascists, who practised apartheid, also massacred hundreds of thousands of Africans, most of whom were North or East Africans. Quoting from Patrick Bernhard’s excellent Borrowing from Mussolini: Nazi Germany’s Colonial Aspirations in the Shadow of Italian Expansionism:

[Reich] publications also justified acts of extreme violence committed by the [Fascist] military in its colonies. Although an estimated 100,000 people died in Libya because of [the Fascists’] murderous anti‐guerrilla policy against Arabs, Berbers and Jews,75 it was first and foremost the war in Abyssinia that received huge attention and media coverage in [the Third Reich]. As we now know, between 350,000 and 760,000 Abyssinians from a population of 10 million died during [Fascism’s] war of aggression and the subsequent occupation.76

During the conflict, which began in October 1935, [Fascist] armed forces under the command of Emilio De Bono and Pietro Badoglio not only made ample use of modern tanks, artillery and aircraft against a poorly equipped Ethiopian army, they also crushed military resistance with naked terror: they bombed undefended villages and towns, killed hostages, mutilated enemy corpses, established several forced labour camps, committed numerous massacres as reprisals, deported the indigenous intelligentsia and used poison gas not only against combatants, but also against cattle. By the end of the Ethiopian campaign in May 1936, the Royal Italian Airforce had deployed more than 300 tons of arsenic, phosgene and mustard gas.

For a documentary partly on the Fascists’ crimes in Ethiopia (partially NSFL), see Fascist Legacy.

In Somalia, the pattern was similar: widespread use of forced labor, use of the concentration camp, violence against dissidents, thousands dead, and forced marriages, among other worries.

Geoff Simons’s Libya: The Struggle for Survival, pages 122–3, 129:

[A Fascist]/Egyptian agreement in 1925 gave [the Fascist bourgeoisie] sovereignty over the Sanussi strongholds at the Jarabub and Kufra oases, making it easier for the [Fascists] to cut off the Libyans’ sources of supply in Egypt, but the conflict continued. The [Fascist] supply lines, communication facilities and troop convoys came under frequent attack, with the [Fascists] responding by blocking water wells with stones and concrete; slaughtering the herds of camels, sheep and goats that the tribes depended on; moving whole communities into desolate concentration camps in the desert; and dropping captured Libyans alive from aircraft.

[…]

There is a lengthy catalogue of war crimes perpetrated by General Graziani, for which he was never called to account. It is suggested that the [Fascists] deliberately bombed civilians, killing vast numbers of women, children and old people; that they raped and disembowelled women, threw prisoners alive from aeroplanes, and ran over others with tanks. Suspects were hanged or shot in the back, tribal villages — according to Holmboe — were being bombed with mustard gas by the spring of 1930. As with all atrocity tales, there is probably an element of exaggeration, but Holmboe noted that during the time he was in Cyrenaica ‘thirty executions took place daily […] The land swam in blood!’41

Few Libyan families survived this period without loss: Muammar Gaddafi himself lost a grandfather, and three hundred members of his tribe were forced by the [Fascists] to seek refuge in Chad. Graziani was well aware that the alleged atrocities, under his command, were tarnishing his military reputation: he noted the ‘clamour of unpopularity and slander and disparagement which was spread everywhere against me’, but recorded in his book, The Agony of the Rebellion, that his conscience was ‘tranquil and undaunted to see Cyrenaica saved, by pure Fascism, from that invading Levantism which sought to escape from the civilising Latin force’.

For an excellent reenactment of some of these events, see The Lion of the Desert (which historian Angelo Del Boca praised, saying that ‘it respects the historical truth’, but no reenactment is perfect, of course).

As the Allies sought to reclaim Libya, a new wave of white supremacist violence erupted, including (maybe surprisingly) against Jews. From Patrick Bernhard’s Behind the Battle Lines: Italian Atrocities and the Persecution of Arabs, Berbers, and Jews in North Africa during World War II:

Anti‐Jewish pogroms broke out in major Libyan towns such as Benghazi and Tripoli: [Fascists] plundered Jewish shops and beat or chased Jews in the streets.34 The governor‐general of Libya himself spoke of “excesses” committed by his compatriots in Benghazi, the capital of Cyrenaica.35 Roberto Arbib, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Tripoli, wrote with regard to the violent assaults he witnessed in Libya’s capital: “[the Fascists] could not stand the sight of a single Jew.”36

Such attacks were almost unique in the history of Italian Fascism: in Italy itself, anti‐Jewish pogroms occurred only rarely. Similar persecution had taken place only in Trieste, in the contested borderland with Slovenia, where local Fascist leaders were fervently antisemitic.37

As for Eritrea, there were not as many obvious atrocities; the Fascists usually oppressed them in subtler ways. One maybe not so subtle way, though, was concubinage. Quoting Giulia Barrera’s Dangerous Liaisons: Colonial Concubinage in Eritrea, 1890–1941:

Generally speaking, Italian men categorized their Eritrean sexual partners as either “sciarmutte” or “madame.”3 Sciarmutta was an Italianization of the Arabic term “sharmãta” and stood for prostitute; the term madama applied to concubines who associated with Italian men, although Italian men and their madame did not always cohabit.

Fascism in the Balkans

Pictured: Fascist firing squad about to execute several Slovenian hostages.

The Fascist assault on the Greek isle of Corfu in 1923, which resulted in at least fifteen deaths, was but a brief taste of what the Fascist bourgeoisie had in store for the Balkans in 1939 and later. Albania, already exposed to Fascist neoimperialism in the 1920s and 1930s, soon succumbed to a Fascist invasion in the April of 1939. The invaders killed at least 160 Albanians, but the actual number might have been as high as 700. Either way, the worst was yet to come. To get an idea of the situation, here is a quotation from Bernd J. Fischer’s Albania at War, 1939–1945, page 114:

In August [1942] Tomori reported further decrees, including “All prefects in Albania are authorized to fix by order the delay during which all rebels in the district of a certain prefecture must give themselves up under penalty of death for infringers. The families of those who do not surrender will be interned in concentration camps, their houses burned and their possessions confiscated. These measures will also be taken for military deserters and for recruits who will not respond to the calling‐up orders.”94

It is difficult to say how many casualties in total the Italian Fascists inflicted, but Axis occupation overall caused nearly two and a half dozen thousand deaths. Pages 267–8:

Casualty figures vary rather widely. One of the first postwar Albanian newspapers, Luftari, estimated Albanian dead at 17,000.23 This figure was later revised upward by official Albanian government estimates and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to between 28,000 and 30,000, mostly from the south, out of a total population of about 1,125,000, or about 2.58 percent of the population. Some 13,000 were left as invalids.24

Now it was Greece’s turn (because apparently the Dodecanese islands from the 1910s weren’t enough to appease the Fascist bourgeoisie). After Fascist Italy’s unsuccessful invasion of Greece in late 1940, the Third Reich seized Greece in April 1941 and transferred it to Fascist Italy. Here are some examples:

They introduced a new tax system, while the judges applied the mandatory [Fascist] law and tried in the name of the Italian king. They opened camps for “disobedient Greeks” in Paxos, Othoni and Lazaretto, where approximately 3,500 Greeks were jailed, tortured and executed under harsh conditions.

[…]

The most characteristic case was the massacre in the village of Domenico, where on February 13, 1943 [Fascist] soldiers burned the village and murdered 194 people, including women and children. Approximately in the same area one month later, on March 12th, 1943, the [Fascists] burned Tsaritsani to the ground and executed 40 villagers. On June 6, 1943, in retaliation for the bombing of a rail tunnel by the resistance in the vicinity of Kournovo (central Greece), the [Fascists] executed 106 Greeks.

Half of Yugoslavia was next. (Possibly NSFL.) Quoting Capogreco’s Mussolini’s Camps: Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940–1943), page 1:

In the Yugoslav territories occupied or annexed after the [Axis] invasion of April 6, 1941, [Fascist] forces often resorted to repressive methods that included the burning of villages, shooting of civilian hostages, and deportation of local people to special concentration camps “for Slavs.”2

Set up in [Fascist] Italy and in the occupied territories, and almost always supervised by the Italian Armed Forces, these camps forced internees to endure a restrictive and harsh internment that led to thousands of deaths, including those of many children.

Page 54:

In Yugoslavia, the Italian Army used civilian internment as part of its violent and deliberately racist occupation that included the burning of villages and the execution by firing squad of civilian hostages, behaviors that created in local populations “a trail of resentment against the Italian community that, still today, hardly abates.”46

For a documentary partly on the Fascists’ crimes in Yugoslavia, see Fascist Legacy.

Some Greeks and Yugoslavs would also, quite literally, share their suffering. Page 29:

Typically, in the reports written by Red Cross representatives, there emerged significant differences in the treatment given to British and French prisoners, and that reserved for Yugoslav and Greek ones. The latter, typically housed in precarious and decrepit structures, often lamented the violations of the articles 36–41 of the Geneva Convention.149 Even when they were in the same camps with British and American soldiers, their conditions often remained pathetic.

Fascism on the Eastern Front

Pictured: Several Soviets that the Fascists killed.

Even Soviet documents acknowledge that the Italian Fascists on the Eastern Front were quite restrained in comparison with their allies; most of them were gentler with the civilians than the other Axis forces. Quoting Bastian Matteo Scianna’s The Italian War on the Eastern Front, 1941–1943: Operations, Myths and Memories, page 248:

Soviet postwar accusations were themselves moderate: only 36 Italians were charged with war crimes,135 and the files show a notable difference between the German and Hungarian actions on the one hand, and the Italians’ on the other: only five per cent of 175 asserted war crimes in the Voronezh area were associated with Italian (Alpini) troops.136

Yet, as that very fragment implies, there were certainly exceptions. Pages 246–7:

The Italians, still, were generally “not regarded as terrible looters during the war,”124 or as prone to rape (as much evidence about the Romanians and Hungarians indicates).125 Nevertheless, the Germans reported “rather unpleasant instances in regards to behaviour towards the civilian population” by the XXXV Corps (former CSIR) when it moved eastwards after a long winter rest,126 and the Italians were involved in oppressive measures such as the burning of villages, shooting innocents, forced prostitution and pillaging.127

But, exceptions or not, the otherwise neighbourly Fascists were still accomplices in a massive colonial war of extermination, and that alone should call their character into question. Page 238:

Undoubtedly, the [Regio Esercito] were no saints and did take part in a war of aggression that resulted in the death of millions of soldiers and innocent civilians.

In sum, Patrick Bernhard’s Renarrating Italian Fascism: New Directions in the Historiography of a European Dictatorship indicates that overall,

One simply cannot forget that over one million people died as a consequence of this vision — mostly in Africa, but also in the Balkans — in the wars of conquest and occupation waged by the Italian Fascist régime.

(Emphasis added in all cases.)