- cross-posted to:

- history@hexbear.net

- cross-posted to:

- history@hexbear.net

I have occasionally said before that the reason that I study Fascism is to educate other socialists about the subject, but that is only partially true. The other reason is that antisocialists (and sometimes even novice socialists) dish out half‐baked Reich–Soviet analogies so repetitively and tiresomely that it is nearly enough to make me lose whatever sanity that I have left, so I have to read various books and scholarly articles on Fascism to explain why the constant analogies are bullshit. Nicolas Werth—in a rare example of anticommunist honesty—said it best: ‘The more you compare Communism and Nazism, the more the differences are obvious.’

Possibly nothing illustrates this better than the relations between German and Italian Fascism. I have discussed before that Benito Mussolini would be a far more logical analogue to Adolf Schicklgruber than either one of them would be to Joseph Stalin, but relations between Fascist Italy and the Third Reich are of very little interest to presumably “antifascist” anticommunists. Perhaps somebody is afraid that a careful examination of the matter would make the German–Soviet Pact of 1939 look incredibly shallow by comparison? Who knows.

Whatever the case, it would hardly be an exaggeration to describe Mussolini and Schicklgruber as friends. As a matter of fact, they met in person more than any of the Allied leaders did! While there were, of course, bouts of relationship drama, much like in many ordinary friendships, it only took a short while before crybaby time was over and those were all water under the bridge (also like in an ordinary friendship).

Benjamin G. Martin’s The Nazi–Fascist New Order for European Culture, only one of the many books on interfascist relations, sums up the Rome–Berlin Axis in particular nicely. Page 74:

On November 1, 1936, Mussolini announced the birth of the “Rome–Berlin Axis.” This announcement marked the culmination of a process of behind‐the‐scenes negotiations between representatives of Hitler and Mussolini that had begun in the summer of 1935. Both [anticommunists] sought an ally to help them escape their international isolation and to offer cover for their expansionist projects.

The turning point had come in December 1935, when [Rome’s] military campaign in Ethiopia ran into unexpected trouble and Mussolini, hoping to distract and divide the British and French, reached out to Hitler’s Germany in an effort to redraw the balance of forces in Europe. [Rome] abruptly called off [its] earlier diplomatic overtures to the French and the Soviets, and Mussolini let [Berlin] know that he would not object if a formally independent Austria were in reality to become a [Reich] satellite.

German–Italian rapprochement accelerated in the summer of 1936 with the outbreak of Spain’s civil war, as Italian and German intelligence officials coordinated their support for Francisco Franco’s nationalist rebellion against Spain’s democratic republic. For Hitler, peeling [Fascist] Italy away from her ties to France and Britain marked a victory in his effort to undermine unified European opposition to [the Fascist bourgeoisie’s] plans for war and conquest.¹

This arguably marks the point of no return for the two Fascist régimes, if not November 1936 then 22 May 1939, at which point the alliance became de jure. If we mark mid‐ or late 1936 as the start of a de facto alliance (a perfectly valid interpretation, given the Reich and Fascist Italian collaboration in the Spanish Civil War), then we can say that the Third Reich and the Italian Fascists were effectively allied for 8 years.

For how many years was the German–Soviet Pact effective? 1.8. 1.8 years. Yes, under certain criteria somebody can argue that the alliance between the Third Reich and Fascist Italy lasted for fewer than eight years, but even if you apply the most absurdly strict criteria it still outlasted the German–Soviet Pact. Yet which one do you find “antifascist” anticommunists discussing more? Which one do you think is more important to them?

The following are only a few examples of official Fascist propaganda and photographs demonstrating the close ties between German and Italian Fascism, close ties that horseshoe theorists almost always have to scribble themselves for their lazy comparisons. Since I cannot possibly provide every example without testing your patience, I’ll limit myself to twenty items:

Parade of Wehrmacht divisions under the Brandenburg Gate decorated with Fascist flags on the occasion of a speech by Schicklgruber and Mussolini at the Olympic Stadium. Dated 28th September 1937.

Italians showing their support for the Third Reich during Adolf Schicklgruber’s visit to Fascist Italy in 1938.

German press photograph of Benito Mussolini receiving a big send‐off in Berlin. Probably from the 1940s.

Members of a Fascist youth organization talking to members of the HJ on the ‘day of fascist youth’ in Padua, 1940.

Adolf Schicklgruber, Hermann Göring, Benito Mussolini, and Galeazzo Ciano.

Another combination of the fasces and the swastika, this time in the form of a solidarity pin. Probably from the mid‐1940s.

A medal that high‐ranking officials presented to Fascist cannon fodder for their action in North Africa.

Photograph of a mass meeting between the Western Axis powers.

Fascist standards at a maneuver, 1937.

Fascist flags fly side‐by‐side in Rome. Dated 1937

A German post stamp featuring Schicklgruber and Mussolini, between a fasces and a German eagle perched on a swastika. It is captioned, ‘Two peoples and one struggle.’

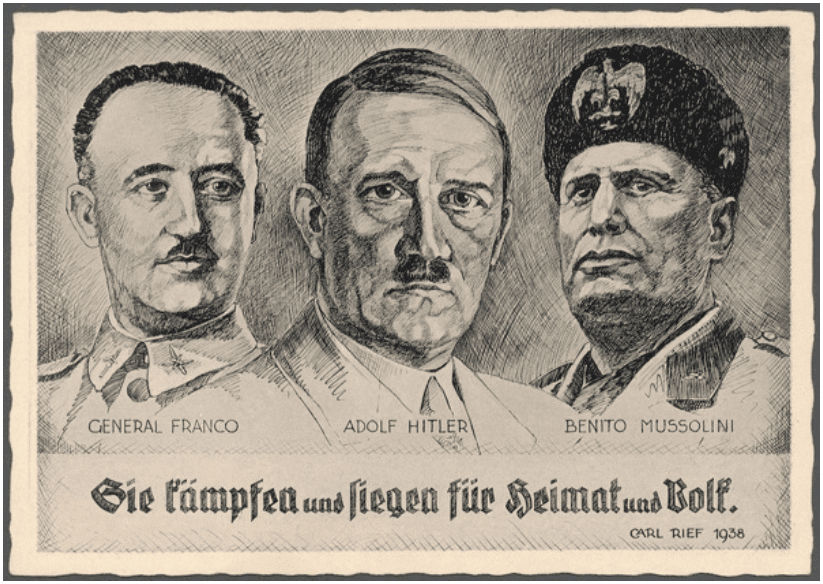

A Spanish postcard featuring Adolf Schicklgruber, Francisco Franco, and Benito Mussolini.

More fascist artwork featuring Schicklgruber, Franco, and Mussolini. It reads, ‘The three great defensive military leaders of peace and civilisation.’

The big three again. Dated 1938.

Neapolitan anticommunists welcoming Adolf Schicklgruber’s visit to Fascist Italy in May 1938.

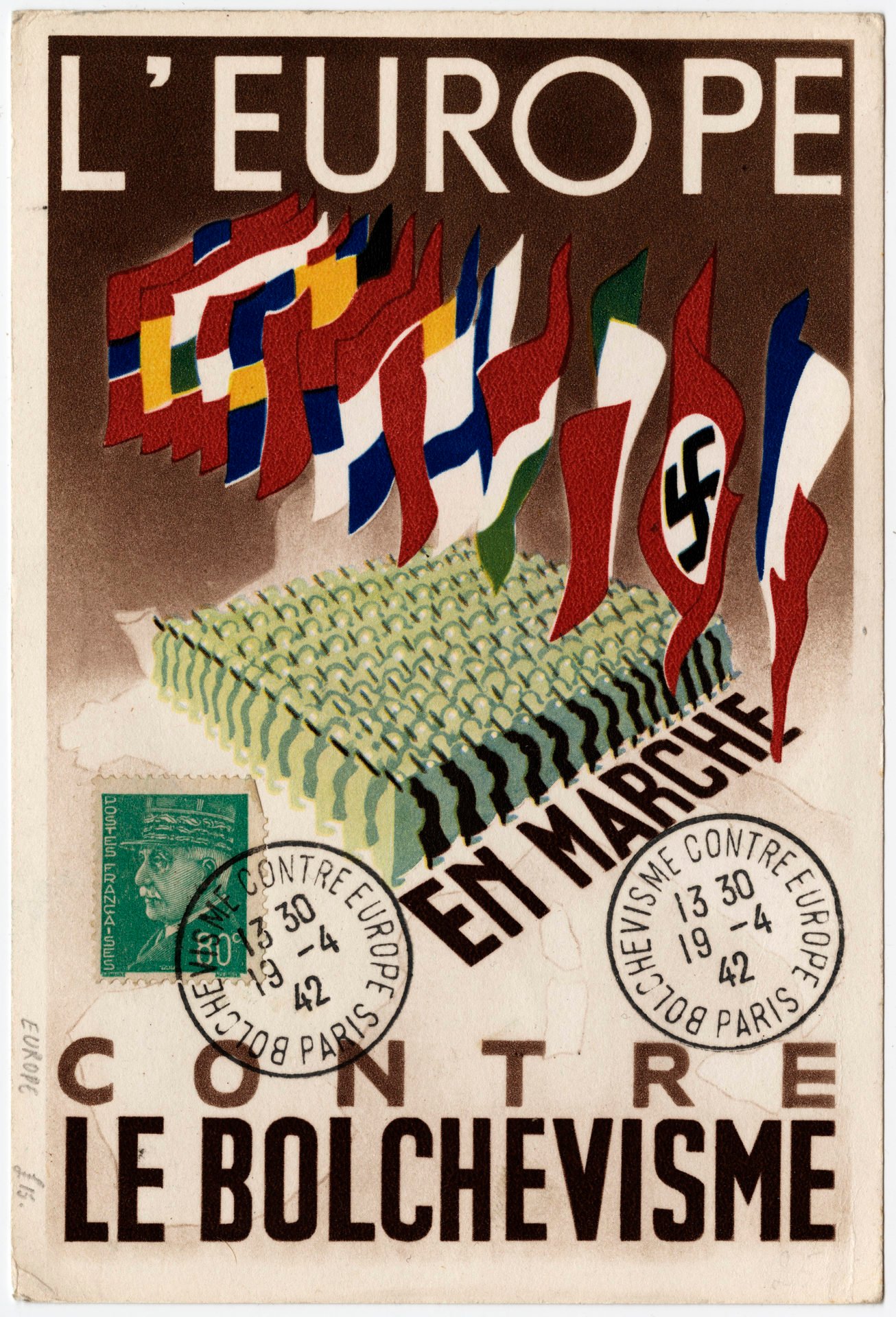

French propaganda depicting fourteen European flags, among them Fascist Italy’s and the Third Reich’s, against the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Operation Barbarossa inspired a great deal of Axis artwork such as this.

Croatian propaganda depicting seven European flags, among them Fascist Italy’s and the Third Reich’s, heading to Victory.

‘Cheerful comrades in arms outside Tobruk in May 1941. ‘German and Italian soldiers’, Leutnant Wilfried Armbruster penned in his diary, ‘just light up when Rommel comes.’ Luftwaffe Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring wrote that the ‘comradeship existing between Italian and German troops can be classified as good, even though at times honest embitterment at the attitude of Italian command and troops clouded the existing friendship.’ According to Rainer Kriebel, ‘It must be stressed that during the fighting around Tobruk not only German, but Italian troops as well, fought with great courage and persistence.’’ (Source.)

Fascist cannon fodder in Athens. Dated 1941.

Another Fascist propaganda poster. It reads, ‘Two people, one war.’

And keep in mind, this brief selection is just photographs and artworks that I’ve found. Examples in audio include how the PNF’s anthem Giovinezza inspired the German song In dem Kampfe um die Heimat, and how the Third Reich’s anthem Horst Wessel Lied in turn inspired the Italian song È l’ora di marciar, but these are only the aesthetics. We must not overlook how the Italian Fascists tutored their German counterparts (in policing and elsewhat). Quoting from Patrick Bernhard’s Borrowing from Mussolini: Nazi Germany’s Colonial Aspirations in the Shadow of Italian Expansionism:

At an early stage, in fact, Hitler maintained that the Jews were a foreign, non‐European element not only in German but also in Italian society. The triumph of fascism in Italy had been a victory for the Italian Volk, Hitler repeatedly said.⁴⁴ It was in Italy that the struggle for racial ‘supremacy’ had been decided: the Jews had lost the battle ‘in Italy as well’. Not least for this reason, there was ‘not another state like Italy today’ so well‐suited to be Germany’s ally. Based on Hitler’s statements, it is clear that the fated fascist alliance also had a racist ideological foundation, and that it should not be understood — as earlier research has so often suggested — as a purely tactical alliance between two major powers that fundamentally mistrusted each other.⁴⁵

Christian Goeschel’s Mussolini and Hitler: The Forging of the Fascist Alliance, page 71:

[Fascist] Italy had become more and more economically dependent on [the Third Reich]. By 1936, 20 per cent of [Fascist] Italy’s exports went to [the Third Reich], a huge increase from the 11 per cent of 1932. German imports, especially coal and other raw materials, to [Fascist] Italy also rose dramatically, from 14 per cent in 1932 to 27 per cent in 1936–8, increasing to 40 per cent in 1940.³⁸ In the wake of the October 1936 announcement of the Four‐Year Plan, [Fascist] Italy began to deploy its workers to the Reich. After negotiations in 1937, more than 30,000 Italian agricultural labourers, most of them jobless at a time of high unemployment in Italy, were sent north.

From their humble beginnings in 1922, to the Four Powers Pact of 1934, the Anti‐Comintern Pact in 1936–7, the German–Italian Cultural Accord of 1938, the Pact of Steel of 1939, the Tripartite Pact in 1940, and their bitter ends in 1945, the German and Italian Fascists—not the Soviets—were useful allies to each other. In the words of Adolf Schicklgruber:

In enumerating these factors, Duce, I should like to begin with what for me, through her people, her system and especially her leader, has always been our foremost friend, and always will remain our foremost friend: Italy!

(Emphasis added in all cases.)

It is no wonder, then, that the German and Italian Fascists fought side‐by‐side in Spain, the Balkans, North Africa, and the Eastern Front!

Consider this my not nearly harsh enough revenge for dullards like Timothy Snyder, Anne Applebaum, Roger Moorhouse, and other antisocialist hacks inflating the hell out of the German–Soviet Pact’s importance while reducing the Rome–Berlin Axis to a footnote—if anything at all, that is. Thanks to them, the ‘European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism’ is a thing whereas nobody remembers names like Galeazzo Ciano, Rodolfo Graziani, Pietro Badoglio, or Mario Roatta, let alone their atrocities in Eurafrica.

Pictured: Joseph Stalin beating an Axis dictator.

Click here for other events that happened today (November 1):

1921: Harald Quandt, Luftwaffe lieutenant, existed.

1933: The Dachau concentration camp commander, Theodor Eicke, put its regulations into effect and it became a blueprint for other camps. Under Article 12, people who refused to work, or shouted while on the job, were to be shot immediately.

1935: Somebody attempted to murder future Axis politician Wang Jingwei and three other officials shortly before he died himself.

1937: The Defense of Sihang Warehouse ended in an Imperial victory while Imperial troops advanced deeper into Shanghai by crossing Suzhou Creek.

1939: Chinese forces launched the Winter Offensive on multiple fronts against the Imperial Japanese Army while a royal decree in the Netherlands established martial law in key regions mostly along the German–Dutch border.

1940: Fascist forces reached the Thyamis River. Coincidentally, Instanbul declared neutrality in the Greco‐Italian War.

1941: Berlin claimed that the United States ‘attacked Germany’ and that its head of state had been placed before the ‘tribunal’ for world judgment; Berlin disputed the Yankee account of the sinking of the Reuben James and claimed that a German submarine only attacked after Yankee destroyers attacked German submarines first. Meanwhile, as the Reich commissioned the submarine U‐214, Axis troops occupied Simferopol on the Crimean peninsula, and Jews in Slovakia were required to travel in separate train compartments and send and receive letters marked with the Star of David.

1942: The Matanikau Offensive commenced during the Guadalcanal Campaign and finished three days later with a Yankee victory. Meanwhile, Axis Army Group A captured Alagir, four Axis sailors escaped from an internment camp at Fort Stanton, the Soviets formed a committee for the investigation of war crimes committed by the Axis, and Strikes broke out in Haute‐Savoie in protest of the Vichy government’s forced recruitment of labour for the Third Reich.

1943: The 3rd Marine Division landed on Bougainville in the Solomon Islands and secured a beachhead, leading that night to a naval clash at the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay.

1944: As British Army units landed at Walcheren, the Axis submarine U‐483 torpedoed Whitaker and rendered a constructive total loss, an Axis kamikaze sunk Abner Read, the Axis lost three ships in the Kvarner Gulf, an F‐13 Superfortress conducted a reconnaissance sortie over Imperial Japan, and the Western Allies commenced Operation Infatuate.

Removed by mod