- cross-posted to:

- memes

- memes@lemmy.ml

The reason that to this day people still name their kids Stalin in India

Also Stalin, in the lead up to the famine:

The Political Bureau believes that shortage of seed grain in Ukraine is many times worse than what was described in comrade Kosior’s telegram; therefore, the Political Bureau recommends the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine to take all measures within its reach to prevent the threat of failing to sow [field crops] in Ukraine.

Signed: Secretary of the Central Committee, J Stalin (Archive of the President of the Russian Federation 1932)

They basically knew that kulaks were sabotaging grain production in the Ukraine.

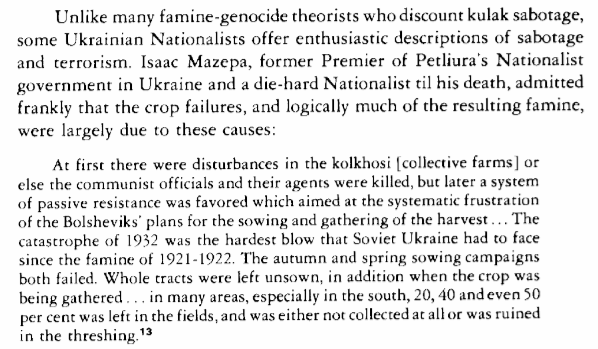

The Ukrainian nationalists also know (and gloat about) the fact that they sabotaged the harvest

Oh right, this reminds me that Keynes, as a British delegate to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles wrote about the state of grain production in the USSR.

While he doesn’t go so far as to say “grain production in the USSR is a ticking timebomb for famine in the region”, what he does lay out is his assessment of the general state of agriculture and the lack of modern farming methods and the lack of infrastructure which I’d say is a very objective and clear indication that all the conditions were right for a catastrophic famine to occur (as was cyclical until the USSR was capable of modernising agriculture and thus eradicating famines in the region.)

Before the war Western and Central Europe drew from Russia a substantial part of their imported cereals. Without Russia the importing countries would have had to go short. Since 1914 the loss of the Russian supplies has been made good, partly by drawing on reserves, partly from the bumper harvests of North America called forth by Mr. Hoover’s guaranteed price, but largely by economies of consumption and by privation. After 1920 the need of Russian supplies will be even greater than it was before the war; for the guaranteed price in North America will have been discontinued, the normal increase of population there will, as compared with 1914, have swollen the home demand appreciably, and the soil of Europe will not yet have recovered its former productivity. If trade is not resumed with Russia, wheat in 1920-21 (unless the seasons are specially bountiful) must be scarce and very dear. The blockade of Russia, lately proclaimed by the Allies, is therefore a foolish and short-sighted proceeding; we are blockading not so much Russia as ourselves.

The process of reviving the Russian export trade is bound in any case to be a slow one. The present productivity of the Russian peasant is not believed to be sufficient to yield an exportable surplus on the pre-war scale. The reasons for this are obviously many, but amongst them are included the insufficiency of agricultural implements and accessories and the absence of incentive to production caused by the lack of commodities in the towns which the peasants can purchase in exchange for their produce. Finally, there is the decay of the transport system, which hinders or renders impossible the collection of local surpluses in the big centers of distribution.

I see no possible means of repairing this loss of productivity within any reasonable period of time except through the agency of German enterprise and organization. It is impossible geographically and for many other reasons for Englishmen, Frenchmen, or Americans to undertake it;—we have neither the incentive nor the means for doing the work on a sufficient scale. Germany, on the other hand, has the experience, the incentive, and to a large extent the materials for furnishing the Russian peasant with the goods of which he has been starved for the past five years, for reorganizing the business of transport and collection, and so for bringing into the world’s pool, for the common advantage, the supplies from which we are now so disastrously cut off. It is in our interest to hasten the day when German agents and organizers will be in a position to set in train in every Russian village the impulses of ordinary economic motive. This is a process quite independent of the governing authority in Russia; but we may surely predict with some certainty that, whether or not the form of communism represented by Soviet government proves permanently suited to the Russian temperament, the revival of trade, of the comforts of life and of ordinary economic motive are not likely to promote the extreme forms of those doctrines of violence and tyranny which are the children of war and of despair.

Let us then in our Russian policy not only applaud and imitate the policy of non-intervention which the Government of Germany has announced, but, desisting from a blockade which is injurious to our own permanent interests, as well as illegal, let us encourage and assist Germany to take up again her place in Europe as a creator and organizer of wealth for her Eastern and Southern neighbors.

[my emphasis]

— The Economic Consequences of the Peace by John Maynard Keynes (1920)

And they did their best to stop them, right?

That’s a good question but i can’t say with certainty because I haven’t looked into the famine with any depth yet.

I know that Kosior, who was the head of the Ukrainian SSR, received serious criticisms for how he managed the Ukraine in the lead up to the famine and during the famine but I really can’t speak with any authority about what happened. Hopefully someone else who knows about this subject will chime in.

Look up the work of Mark Tauger. He is an economic historian who specializes in the period.

He describes the worst human-driven cause of the famine being the mass slaughter of livestock, cattle but also very importantly mass slaughter of horses used for meat and labor, by kulaks and Ukrainian nationalists.

He also describes the relief efforts made by the Soviets, especially once the higher leadership in Moscow began taking a more active role as the crisis deepened.

Thanks comrade, can you please share the sources with me?

A lot of his essays have been collected here

He’s an academic so you also find a lot of his work on libgen especially if you search journals.

https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/169438

I can also toss in more citations later in the day too if requested

Removed by mod

Oh shit ya found the source material!