One morning the police called. What could this have to do with me? Nothing. I told them that I couldn’t come, I was too busy working. Ten minutes later, the police called again. I repeated that I’d come by soon. But they said that it was very urgent.

I thought, ‘What could they want?’ So I went to the police and they showed me a letter. ‘Here, read this,’ they said. ‘Bavarian Political Police.’ What did that have to do with me? ‘You are suspected of being homosexual. You are hereby under arrest.’ What could I do? Off I went to Dachau, without a trial, directly to Dachau. I spent a year and a half in Dachau without really knowing why.

[…]

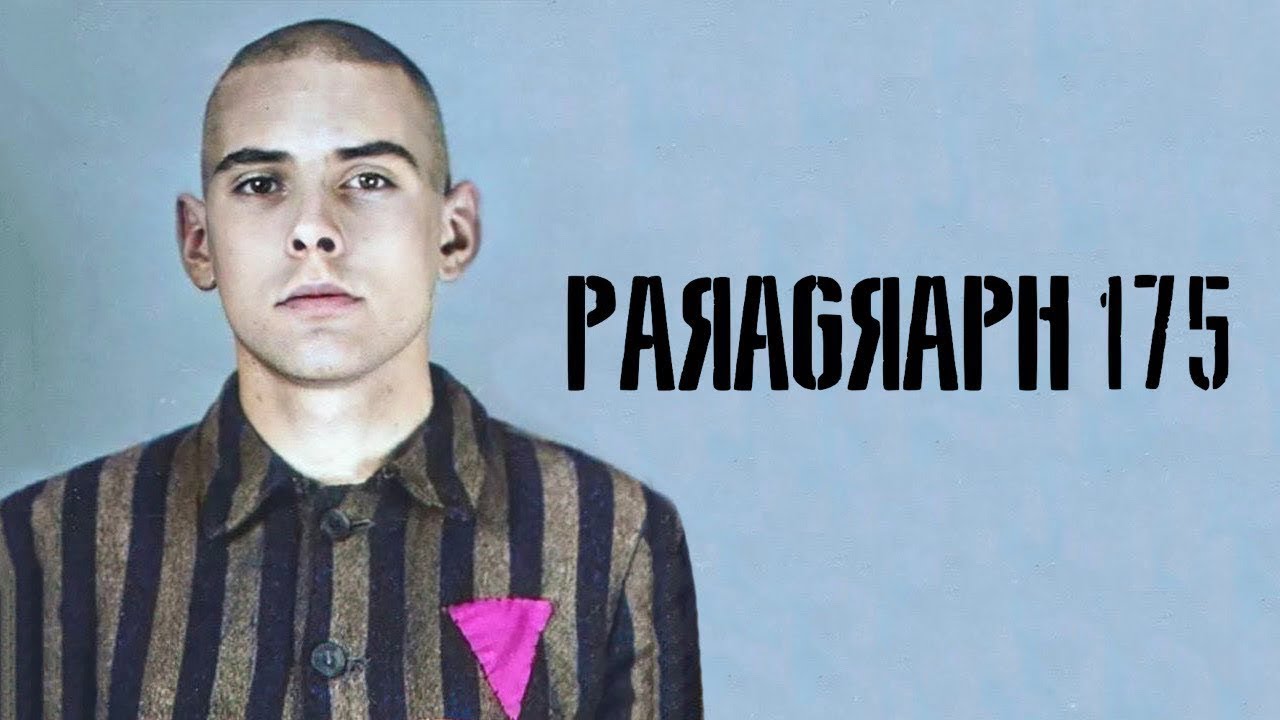

Under the [Fascist] version of paragraph 175, gossip and innuendo became evidence. Men could be arrested as homosexual for simply a touch. A gesture. A look. No‐one knew how long he’d be held, or where his arrest would lead him: to prison, or a concentration camp.

After I was released from Dachau, I went on a trip. I think that I was being watched… this woman was always behind me. I left my hotel to go eat and a hustler came up to me. I realised that I was being followed. He pulled me into some bushes. I said, ‘Someone is following us.’ ‘No,’ he said. ‘No‐one is there.’ And that’s when it happened. ‘You are under arrest.’ I was taken somewhere for some prison, for trial. I didn’t understand anything. And… while I was there, almost all the homosexuals were transported to Mauthausen, and nearly all of them… were killed.

(Tagged as NSFW for some scenes involving nudity. For more on Gad Beck, one of the interviewees, click here.)

Quoting Ken Setterington’s Branded by the Pink Triangle, chapter 7:

For Jews, the matter of sexuality was of little importance: Jews were targeted for extermination whatever their sexuality. During the first years of the [Third Reich], a gay Jew was more likely to be arrested and punished as a homosexual than as a Jew. But once the [Fascists] began to persecute the Jews, Jewish [gay men] and lesbians were simply rounded up as Jews. It was easier to hide one’s homosexuality than it was to hide the fact that one was Jewish.

Still, there were those who were able to go into hiding with the help of friends and support from outside of [the Reich]. Gad Beck, a homosexual Jew, was able to survive through his determination, strong connections, and extreme good luck.

With an Austrian Jewish father and a Christian German mother who had converted to Judaism, Gad Beck and his twin sister were mischlings (only part Aryan) and not as strongly targeted when the [German Fascists] began their assault on the Jews. Gerhard (as he was first named) and his twin sister, Margot (later called Miriam), were born in Berlin in 1923.

Gerhard knew from a very early age that he was attracted to boys. He was not sexually shy with males and had many pre‐teen and teen crushes on boys and men. His parents were understanding and knew that their son was a homosexual at an early age.

In 1936, when Gerhard turned thirteen, the age at which Jewish boys have their bar mitzvah, the Beck family threw an event for Gad that was to be their last happy family celebration. After that their lives changed for the worse. Gerhard’s father lost his job and Gerhard had to go to work because there wasn’t enough money for his school tuition. Life was hard for him in the next few years, but it was relatively stable. The Beck family was even able to enjoy the success of an Austrian relative, Walter Beck, who won a bronze medal in the Berlin Olympics.

When the [Third Reich] annexed Austria in 1938, life for the Becks changed even more dramatically. They were evicted from their home and forced to find a place in a segregated area for Jews called a Judenhaus (Jews’ House). The Becks had considered emigration, but by then it was much too late: Jews were not allowed to leave [the Third Reich] and only those with money and connections could even hope for the chance to go somewhere else.

On November 8, 1938, when the riots that became known as Kristallnacht destroyed Jewish businesses, residences, and synagogues, it was clear that life for Jews living [under Fascism] would never be the same. By 1939, they were being turned into [neo]slaves of the [Third Reich], and the Jews in Berlin were conscripted to work in the [Fascist] armaments industry.

Gerhard and his sister had the good fortune of being able to join a Hachshara, a Zionist preparation and training center for young people planning to emigrate to Palestine. The Zionists were still running the Hachsharas in 1940, and by 1941, close to 40,000 young Jews had gone to Palestine. Gerhard and Margot were accepted into the program in May of 1940. It was there that they took their Hebrew names, Gad and Miriam. They trained for life in Palestine, but restrictions on emigration made the journey impossible. Though Gad was unable to go to Palestine, he continued to be involved in the Zionist organization.

It was in one of these groups that he fell in love with a young man named Manfred Lewin, whom Gad remembered as being of medium height, athletic, with brown hair and eyes. The two teens were cast in a theatrical reading of the play Don Carlos. One weekend, when the group was practicing in the building that was the former Jewish Teacher’s Association, they camped out on the roof. They had brought food, sleeping bags, and a guitar. They couldn’t go on a camping trip to the country as they had in the past, so this rooftop adventure was the next best thing.

That night up on the roof, the two boys kissed. Gad was in love, but Manfred, while also in love, had difficulty accepting their physical relationship. Gad, however, was persuasive and persistent, and they continued their relationship. Around the time of Gad’s birthday in June, Manfred admitted to Gad, “With you it’s okay.” (37) It was to be Gad’s best birthday present. They were together through the summer.

In 1941, the [Axis] began deporting Jews from Berlin. Gad and Miriam were doing forced labor in the armaments industry. As they were mischlings, they felt a small degree of safety. Still, Gad saw his Jewish friends being deported almost daily. He was aware that some had gone into hiding, but for many Jews it was impossible to leave their parents and grandparents, brothers and sisters. Manfred and his family received their deportation notice in the fall of 1942. Gad knew that he had to act fast. He couldn’t imagine a future without Manfred.

Gad went to Manfred’s employer, a painter named Lothar Hermann. Gad explained that Manfred had been picked up by the [Fascists]. Hermann had lost many employees in this manner, and he thought well of Manfred. He didn’t want to lose a good worker. He told Gad he had an idea — “if you have the nerve.” (38) Gad said he would do anything to free Manfred.

Hermann’s plan was ingenious, but extremely risky. Hermann had a son who was a member of the [HJ], and he said there was a [Fascist] uniform in his house that might fit Gad. It didn’t. It was actually four sizes too big, but Gad made makeshift alterations tucking up the sleeves and the pants on the inside. He wore the uniform to the assembly hall where the Lewins were being held.

The hall was in Gad’s old school and was being used to hold Jews prior to their deportation and ultimate death. It was crowded at the entrance where many people were asking about their relatives. Some tried to bribe the guards for their relatives’ freedom.

“Heil Hitler!” Gad announced as he arrived and asked to speak to the officer in charge. He quickly made up a story about how Lothar Hermann was renovating apartments and how the Jew, Manfred Lewin, had hidden the keys to several units. Hermann now needed Manfred to show him where the keys were so that the workers could get back to renovating.

The story worked and Manfred was brought out to Gad. The officer instructed Gad to bring Manfred right back.

“What would I want with a Jew?” Gad retorted. (39)

The two boys made their way down the street away from the school. Gad was elated. He had just saved his boyfriend from deportation! Gad gave Manfred twenty marks, telling him to go to his uncle where he would be safe until Gad could come for him.

Manfred shocked Gad when he calmly replied, “I can’t go with you. My family needs me. If I abandon them now, I could never be free.” (40)

Manfred had made his decision. Without a smile or a tear — without even a good‐bye — he turned and went back to be with his family, leaving Gad on the street in his borrowed Nazi uniform. “In those seconds, watching him go, I grew up,” wrote Gad years later. (41)

Gad Beck never saw Manfred Lewin again. For the rest of his life, he kept a small notebook given to him by Manfred. In this precious book, Manfred had written poems and notes and made drawings about events in their relationship.

With each passing day, life grew more difficult for Gad, his family, and any Jews living in Berlin. Gad now worked during the day unloading potatoes as they were brought into the city. It was tiring work, but at least he hadn’t been deported. What little free time he had was spent assisting in the underground network that helped Jews who had gone into hiding. The network relied on the support of many people. Some helped because it was the right thing to do; others helped for the money they could make; and some assisted because of their anger at the [Third Reich].

In the apartment building where the Beck family lived, there was an unused attic where Gad had taken in other young Jewish men who needed a place to hide, and where he and Manfred met. Gad had always been very careful when bringing anyone home because there was a tenant in the building, a young German named Heinz Bluemel, who constantly wore his [Axis] uniform. Heinz was a handsome youth, but had a prominent hump on his back. He kept a careful watch over the goings on in his building.

One night when Gad was returning home, the air‐raid sirens began wailing. Heinz, in civilian clothing, hurried Gad to the basement. When the danger ended, Heinz asked Gad to join him on a tour of the building, to make sure there wasn’t any damage. It was in the attic that Heinz told Gad he had known about the trysts there, but had chosen not to denounce Gad. With tears streaming down his face, Heinz revealed that the [Fascists] had forbidden him to wear his [Axis] uniform.

Because of his hump, he was a “defective” — not a shining example of Aryan masculinity. Heinz asked if he could help Gad and his friends, and he made his sexual interest in Gad abundantly clear. Heinz became a messenger for Gad and those in the underground.

Gad went into hiding and became part of a group that was known as Chug Chaluzi (Circle of Pioneers). Founded in 1943, the illegal youth group supported Jews in hiding. Group members helped each other obtain food, false ID cards, and places to stay. Gad and others in the group survived on wit, courage, charm, and luck. The group also depended on wealthy or well‐connected patrons who could do them favors, and who often expected favors in return.

One of Gad’s benefactors was a wealthy engineer named Paul Dreyer. He found Gad a place to stay and always brought bread or meat or some other food when he came calling. No living arrangement was secure, but Gad stayed hidden in a variety of locations and survived until 1945. Then his luck ran out. He was arrested by the SS and thrown into prison in the last few weeks of the war, just before the [Western Axis] surrendered.

Many who had helped him were also arrested in a major round‐up. Paul Dreyer was arrested and accused of treason for aiding and abetting Jews. In his defense Dreyer said that he didn’t know he was helping Jews — he had merely given the young men food because they were such attractive boys. It made no difference. The interrogators realized Dreyer was a homosexual. They set their specially trained dogs on him. Gad was much more fortunate; he was only imprisoned and repeatedly interrogated. He survived and was liberated when the Allies arrived in Berlin.

Further reading: An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin.

Click here for events that happened today (June 5).

1894: Günther Altenburg, Axis war criminal, was born in Königsberg.

1895: Heinrich Kreipe, Axis commanding officer, was born in Niederspier, Thüringen.

1920: Tak Kyonghyong, Axis aviation cadet, was born in Gyeongsangnam Province.

1932: Chancellor Franz von Papen lifted the prohibition on the NSDAP’s SA organization.

1934: As the flagship of Rear Admiral Wang Shouting, with a training crew, Ninghai arrived at Yokohama to attend the funeral of Admiral Heihachiro Togo. Upon the completion of the funeral, she set sail for Harima for an overhaul.

1936: The Esterwegen concentration camp closed for its conversion into a punishment camp. In the meantime, the German anticommunists ordered Esterwegen’s prisoners to build the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

1938: Jozef Tiso gave a speech in eastern Czechoslovakia, and Ernst Udet claimed the 100‐kilometer closed‐circuit landplane speed record flying the Heinkel He 100 V2 aircraft.

1939: Imperial bombers attacked Chongqing, China for three hours during the day; 4,400 people died of asphyxiation in a collapsed air raid tunnel during this bombing.

1940: The Third Reich began the second phase of the invasion of France, Fall Rot. One hundred thirty infantry divisions and ten armored divisions attacked cross the Somme and Aisne Rivers. Jaguar completed escorting battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst and the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper between Kiel and the Skaggerak. Comandante Cappellini arrived at Cagliari, Sardegna at 0200 hours, Comandante Faà di Bruno departed La Spezia at 0420 hours (starting her first war patrol), then Morosini departed Naples at 1800 hours (starting her first war patrol).

1941: Axis submarine U‐48 sank British ship Wellfield hundreds of miles north of the Azores at 0131 hours, leaving eight dead but thirty alive. Before dawn, Axis bombers (unsuccessfully) attacked Birmingham, England, then the Axis announced that it captured 15,000 British and Commonwealth prisoners of war at Crete, Greece. As Axis luxury ocean liner Hikawa Maru departed Yokohama for Vancouver, with some Jewish refugees on board, the Kriegsmarine issued orders for 102 new submarines to be constructed. The Axis lost its gunboat Valoroso and two small transports, Frieda and Trio, to Allied firepower. Most disturbingly, Axis aircraft flew more than twetny sorties against Chongqing, China over a three‐hour period, dropping bombs on civilian sections of the city. In the Jiaochangkou air raid shelter tunnel, more than one thousand Chinese died from asphyxiation.

1942: The SS reported that its mobile gas vans had thus far exterminated 97,000 people. Likewise, the Axis continued the aerial and artillery bombardment of Sevastopol with weapons such as the 800mm railway gun Schwerer Gustav, and five thousand Axis security troops tracked down a destroyed a 2,500‐strong partisan group in the Roslavl and Bryansk region of the Soviet Union. Kurt Daluege became Deputy Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, but the Axis lost its naval personnel Joichi Tomonaga, Ryusaku Yanagimoto, and Tomeo Kaku.