You can use the auto-generated translated captions if you want to watch. I tried to clean it up, but because the subject matter is in Russian, the core of the issue just doesn’t transfer to English. Basically the dude compares a modern textbook to a textbook by Kostin from 1953. The 1953 Russian textbook starts with a straightforward exposition about stressed and stressed vowels and how to check them in the root word, and gives 10s of examples for each of the 5 vowels.

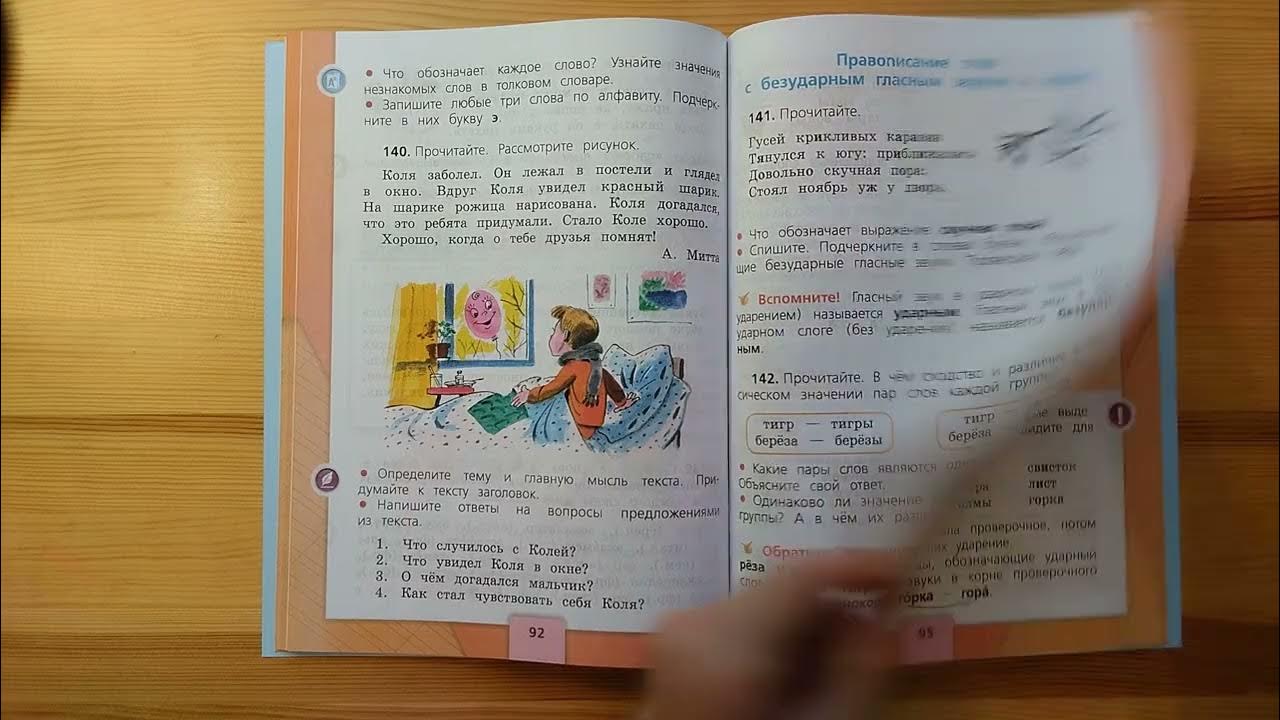

Then comes the new textbook by Kanakina and Goretskiy (the uploader includes his conjecture about why they included Goretskiy on the cover). It is overloaded with pictures, and every page has a “Remember!” and “Pay Attention!” blurb attached, which dilutes their meaning.

He then makes a point to demonstrate what he calls “inappropriate theorizing”. The fat orange blurbs all have some dense wall of definitions, and they themselves are not clear. Seems like an attempt at introducing rigor that is misplaced. The other blurbs about remembering and paying attention are also written obtusely. This is a textbook for 8 year olds, if I haven’t mentioned yet.

This doesn’t seem to be a unique thing, many teachers in Russia and other post-Soviet countries have observed this mangling of Russian, math, and natural sciences textbooks. This video is viral on Russian internet.

I think the idea comes from the fact that fluent adults generally do not need to phonetically decipher words letter-by-letter, but rather recognize them instantly, probably by some combination of shape and context. So memory and context is how good, fast readers actually read usually, thus when you want to teach someone to become a good reader, you may conclude that you need to teach them that. The problem is, of course, that (a) people have not actually deliberately memorized all those words, but rather, these instant brain connections have automatically formed through years and years of reading, and (b) when this strategy fails for an unfamiliar word, a good reader will very much fall back on the letter-by-letter deciphering.

This idea is perhaps more attractive for English educators, than it would be in some other language, because the relationship between spelling and pronunciation is rather more complex (or “loose”) than in many other languages.

But yeah, I do wonder if these people just totally forgot how they themselves learned to read, and also, it very much flies in the face of empirical evidence.