I have been gathering some information about the transatlantic dispute over the Siberian gas pipeline in 1982, in which the Soviet Union sought to build a pipeline to export gas to Europe, in exchange that European companies help with the pipeline’s construction (such as by selling parts and technology). My main reason for interest in this is to add context to the fate of Nord Stream 2 (like the comparison in this 2021 article for example).

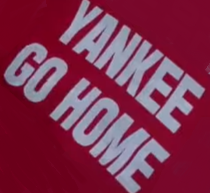

Europeans were happy with the pipeline deal of the 80s, while the US railed against it, applying sanctions widely on several European companies in an attempt to prevent the pipeline from being built, which was resented by the Europeans who had consented to the pipeline deal, wanted more diversity in their energy sources outside of OPEC, and trusted the Soviet Union to deliver them a good service. The US viewed it as an unacceptable deal because it would enrich the Soviet Union and make Europeans “dependent” on Soviet energy, rather than on the OPEC countries for energy.

Current US Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrote a ~200 page book about this in the late 80s, after the US attempts to foil the pipeline’s construction were unsuccessful. His book, Ally Versus Ally, focuses on the fractures among the Western countries over their differences surrounding trade with the Soviet Union and around oil and gas trade in general. He writes that such problems are inevitable in the Western alliance, with the NATO countries only being able to act in a united fashion during wartime or acute tension, while during peacetime, the nature of their relationship as competitive allies breeds disunity, with Europeans naturally tending to want trade with the East, and the US opposing it. He describes this inherent disunity as “a constant weakness in our competition with the Communist world.” He writes:

It might be tempting to view the alliance crisis over the pipeline as an unpleasant but insignificant melodrama that should now be relegated to a footnote in history books. That would be a mistake. What sets the pipeline crisis apart from other alliance squabbles is the fact that it manifested a fundamental difference between the United States and the western Europeans with regard to their policies for East-West relations. These differences date back to the creation of the Western alliance, but came to the fore only in 1982. While the pipeline dispute itself was settled, the larger West-West antagonism of which the crisis was but a symptom remains. […] In fact, the intra-alliance antagonism is almost certain to produce more disputes like the one surrounding the pipeline, as Europe’s export markets continue to shrink and new opportunities for trade with the Eastern bloc open.

It takes two to trade. The Europeans are willing, the United States opposed, or hesitant at best. For this reason, a dispute within the West is almost certain to arise once again, perhaps over the very next megaproject. But whether it will be contained, as the pipeline crisis was, and at what price, is anyone’s guess. This danger facing the alliance can be averted only if the lessons of the pipeline chapter are understood and acted upon.

The United States and western Europe are partners in a competitive relationship among themselves and in an adversary relationship with the Communist world that will continue into the indefinite future. From time to time, unilateral policies, whether self-serving or sincerely meant to benefit the alliance as a whole, only manage to harm Western economies and breed disunity within NATO. Too often, the Soviet Union and its satellites stand idly on the sidelines, watching the allies attempt to hang each other with a rope of their own making.

I haven’t finished reading this book yet, but so far it has covered several angles of the pipeline issue. He is writing in the context of the Cold War and the debate over detente, containment, rollback, etc., but also writing about energy producing countries in general, going into detail about which countries hold what amount of natural resources and how long those resources can last them, etc., and talking about whether the US concern regarding the Soviet Union should be to deny them short term profits or allow them to drain their natural resources by selling them to the West, and how to get US objectives met without causing too much damage to NATO/the Western alliance–basically, he talks about the various points of view on how long Europe’s leash should be and why. He also talks about how the US can benefit from buying oil/gas from other nations until the resource is drained from other countries, at which point the US can really tap into its own resources. Also, it’s interesting to read his view on what level of interrupted energy delivery is acceptable–basically, if energy cutoff is mainly affecting civilian residences rather than military or industry, it’s not a big concern. This comes up in the book because one of the major arguments the US was making was that the Soviets would be able to cut off gas delivery service to Europe. Blinken actually spends some time writing about how historically, the Soviets have actually been quite a reliable trade partner who didn’t tend to use energy trade as a threat.

I just thought I would share this here in case anyone else is interested in it. I haven’t finished the book yet. I also haven’t yet read The Grand Chessboard but I think that’s another one that will add context for this (and various other things), so I plan to read it eventually (Wikipedia: “Regarding the landmass of Eurasia as the center of global power, Brzezinski sets out to formulate a Eurasian geostrategy for the United States. In particular, he writes that no Eurasian challenger should emerge that can dominate Eurasia and thus also challenge U.S. global pre-eminence”).