His name was Ferdinand Ďurčanský, a vocal promoter for Slovak separatism and collaboration with the Third Reich.

Ďurčanský manifested particular skill at propaganda. Ferdinand and Jan Ďurčanský established the radical publication Nástup (Line Up!) and served as its editors in the early 1930s. The periodical railed against “Marxism” and called for improved relations with […] governments such as Germany’s after the [Fascists] came to power [there] in 1933.

[…]

After Munich, Fr. Jozef Tiso, simultaneously prime minister and minister of the interior, appointed Ďurčanský minister of justice, social affairs, and health in the Slovak Autonomous Government (October 7–December 1, 1938), his first major governmental post.

[…]

After expressing gratitude to the Führer for making Slovakia’s self‐determination possible, Ďurčanský also hinted that the “Jewish problem [there] will be solved as in Germany,” and promised to ban the Communist Party. In a secret post‐meeting Foreign Office memorandum, Göring was supportive, saying that “a Czech State minus Slovakia is even more completely at our mercy.”

Ďurčanský was instrumental in the splitting of Czechoslovakia, which facilitated the Fascist bourgeoisie’s gradual conquest of Czechia:

He continued to work for the breakup of what was then called Czecho‐Slovakia. On March 13, 1939, Ďurčanský and Tiso had final discussions with Hitler and von Ribbentrop, and on the next day the Slovak Parliament declared independence. Tiso appointed Ďurčanský foreign minister of the new Slovak Republic the same day. On March 15th Germany invaded the Czech provinces, proclaiming the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” the following day.

Especially relevant for Ďurčanský’s new position—and for the new relationship between Germany and Slovakia—a subsequent “Treaty of Protection” mandated that Slovakia would “at all times conduct its foreign affairs in close agreement with the German Government.” Ďurčanský began negotiations with Göring, signing an agreement on economic and political cooperation with the new Protectorate.

From a summary of the bourgeois state’s persecution of Slovakian Jews:

The most severe antisemitic assaults did not occur until 1942 (if one does not count the abortive 1938 deportation of 7,500 Jews), but already upon the establishment of the autonomous government in 1938 both spontaneous and systemic measures had begun.

Ďurčanský’s Ministry of Justice dismissed 500 Jewish students from Bratislava University in early November 1938 on the pretext that they were “Communists.” Attacks on Jewish‐owned shops—many promulgated by the ethnic‐German minority—began simultaneously

[…]

Unique at the time was Slovakia’s employment of “commissars” to appropriate Jewish‐owned businesses. These figures usually were Hlinka Party members or associates, assigned to manage or at least share decision‐making with the owners of successful Jewish‐owned enterprises. After “assisting” for a time, the commissar usually then forced the Jewish owner to sell out for a fraction of the business’s worth.

[…]

The anti‐Jewish legislation and agitation spurred popular violence against Jews, and even before Slovakia formally declared independence in March, Jews began to flee, many boarding trains for Prague, where the situation was also bleak, but nonetheless perceived as better.

Another significant wave of violence began in August 1939. While some sources place most responsibility on the minority German Party, the Slovak government made no effort to prevent abuses.

The Fascist bourgeoisie deemed this oppression as too moderate; the worst was yet to come:

Despite his scapegoating of the Jews and his earlier promises to Göring, Ďurčanský’s approach to the Jewish Question in particular seemed far too soft.

The German minister to Slovakia, Hans Bernard, complained that Ďurčanský was slowing solution of the Jewish Question, observing that the Jews “are still looked upon [there] as valuable and indispensable fellow citizens” […] The [Third Reich] acknowledged that Ďurčanský was personally responsible for posting “Jews not wanted” signs in Bratislava, but considered such steps insincere, motivated by “opportunism.”

Like many Axis personnel who survived the 1940s, this bourgeois fascist dishonestly presented himself as being a moderate all along:

The Germans discussed the matter in Salzburg in July 1940 and then prevailed upon Tiso to replace Ďurčanský with the more radical Vojtech Tuka as minister of foreign affairs and Alexander Mach as minister of interior.

From 1939 to 1944 Ďurčanský remained in Bratislava, where he practiced law and from where he directed a chemical and pharmaceutical enterprise in Leopoldov, 60 kilometers from the capital. Years later he utilized the German documents of the Salzburg meeting to present himself as a “friend” to the Jews and an anti‐Nazi.

As the war turned against [the Axis], Ďurčanský may have started to experience doubts. Still, he opposed the Slovak National Uprising against Germany that broke out in 1944, despite the fact that he was no longer in the government.

Ďurčanský’s renewed public support for the Tiso régime began on January 14, 1945, when he organized a congress of young Slovaks in Piešťany to reaffirm separatism and hope for a German victory.

In subsequent months he helped propaganda chief Tido J. Gašpar conduct media campaigns against the insurgents, depicting them as bandits, traitors, and criminals. In anticipation of Germany’s impending defeat, Ďurčanský made an informal pact with other Slovak collaborators to continue from abroad the struggle for independence from any reunited postwar Czechoslovakia.

On April 3, 1945, Ďurčanský and other Slovak leaders, including Tiso and Mach, fled into Austria and settled for a time in the town of Kremsmünster.

Notice how all of the states in which he sought refuge were liberal (and Western) régimes:

By September 1945 Ďurčanský had returned to Austria and was living near Steyr. He soon eluded pursuers, however, by changing his residency to Switzerland, to France, and then to Italy. The best evidence has him in Rome early in 1946.

There, despite help from the Church, Ďurčanský feared apprehension by either Czechoslovakian or Soviet agents, and so left Rome’s immediate environs in December, staying first at the Jesuit monastery in Frascati and then moving to the College for Oriental Priests in Grottaferrata.

Unsurprisingly for us, the post‐1945 Italian government had no interest in doing anything about this fascist:

The Czechoslovakian government ordered Major Josef Ruprich, a representative of the Ministry of the Interior and first secretary of the Czechoslovakian legation in Rome, to kidnap Ďurčanský and return him to Czechoslovakia, but his attempt failed. The Beneš government in Prague issued an extradition request but the Italian authorities did not pursue Ďurčanský because the 1922 extradition treaty between the two nations excluded “political criminals.”

The Anglosphere’s authorities were just as enthusiastic:

American and British officials made lukewarm efforts to find and arrest Ďurčanský. […] The [galaxy‐brain] British representatives preferred that Prague approach the Italian government or the Vatican—depending on where Ďurčanský could be found—Echols also recommended that the State Department reach agreement with the British Foreign Office, after which the Ďurčanský case could be reconsidered by the CCAC. The only U.S. official still pushing hard for Ďurčanský’s arrest was Ambassador to Czechoslovakia Laurence Steinhardt.

Pop quiz: where else did Ďurčanský seek refuge?

Go ahead, guess!

If you said ‘Argentina’: Ding‐ding‐ding‐ding‐ding!

Rebuffed by the United States, and desperate to escape Europe, Ďurčanský sailed from Naples to Buenos Aires under the pseudonym of Mandor Wilcsek in August 1947. The Argentinean government helped to subsidize a firm in which Ďurčanský invested—“Alkaloides Argentinos.”

The company had been formed to invent a new process to produce morphine. In addition to evading justice, Ďurčanský selected Buenos Aires to proselytize an independent Slovakia, making that city the headquarters for the SLC.

Aside from this, he did some other work for the Argentinian ruling class:

Ďurčanský’s other work in Argentina centered, supposedly, on penetrating Slovak Communist organizations at the urging of Perón and the police, utilizing emigrés pretending to be leftists. Ďurčanský subsequently compiled lists of alleged Communists and turned them over to the government. He also worked with the Slovak Catholic Association of Buenos Aires, organizing for instance several events to commemorate the first anniversary of Tiso’s death.

Ďurčanský proposed what millions of anticommunists today would still consider great ideas:

Prior to his return, he penned a letter to the Central European Section of the U.S. State Department along with a plan he had authored in London in December. The plan was entitled “Explanation of the Necessity and Way of the Inclusion of Nations behind the Iron Curtain into the Liberation Fight against Moscow.”

That battle would be fought as a struggle for liberation of “enslaved” peoples; Ďurčanský even called for the nuclear destruction of the Kremlin, to be followed by “a general insurrection on the territories of the nations striving for independence.”

The document called for the “military training of refugees without delay,” and further argued that “the training of refugees as paratroupers [sic] would cost less than taking people from employment in the U.S.A., Great Britain, or France and forming such units from them.”

(Emphasis added.)

Now we come to the crux of this adventure:

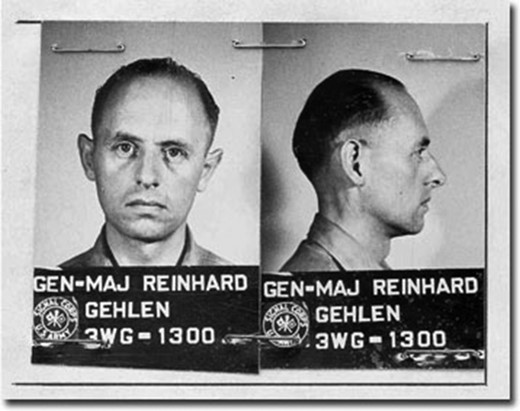

The U.S.‐sponsored Gehlen Organization informed the CIA as early as 1950 that it was considering Ďurčanský for operational use. Dr. Ctibor Pokorný, chief operating officer of the SLC in Germany, met with CIA officials at this time to offer SLC intelligence assets to the agency, including 800 armed men in Slovakia, in return for Ďurčanský’s housing and financial support.

[…]

The Gehlen Organization analyzed Ďurčanský’s potential to deliver usable intelligence in an April 18, 1952 memorandum, comparing him with other Slovak separatists, including Sidor. While Gehlen’s group regarded Sidor highly, it believed that Ďurčanský had more potential because he had stronger control over his organization, the SLC.

[…]

Gehlen’s group believed that Ďurčanský could help them broaden and intensify their Czechoslovakian intelligence activities, as the most “popular” exile leader among the Slovak people and a man with an “uncompromising” attitude in “difficult situations.” They also believed that Ďurčanský’s political activities offered “excellent possibilities [of] sabotage within Czechoslovakia.”

Some CIA officers were reluctant to touch Ďurčanský with a ten‐foot pole, seeing as how Gehlen’s reliability had been spotty and Ďurčanský was likely to provoke infighting among Czech and Slovak anticommies alike. Nonetheless, Gehlen had his way, and Ďurčanský arrived in Germany, where

almost immediately after arrival, Ďurčanský started behaving in a manner inappropriate for an intelligence asset, making his political objectives widely known. Before even meeting with Gehlen’s representatives in Wallersee, Ďurčanský journeyed to Linz and drew the attention of the Czechoslovakian government, whose representatives believed his purpose was to visit Slovak saboteurs and “plot against the People’s Democracy.”

It had not been difficult for them to learn of Ďurčanský’s presence because he was already broadcasting on Voice of America, calling for “terror and espionage” groups in Czechoslovakia to overthrow the government. Gehlen’s people should have ended the relationship at that time.

But they didn’t, because, after all, surely we deserve a break every one and a while from anticommunist efficacy. The CIA was right: Ďurčanský pissed off his fellow anticommunists by accusing Radio Free Europe’s Czech personnel of being ‘Communist collaborators’, thereby complicating his entry into Germany. No worries: Gehlen sent a few representatives to meet him in Austria, where he

persuaded the Organization that there were many patriotic young Slovaks who hated “Bolshevism” and the Czechoslovakian government, and who would risk their lives to help overthrow the régime. Although Gehlen’s group wanted to investigate Ďurčanský’s “friends and followers” more closely, the organization believed in their likely usefulness.

The CIA wanted an intelligence asset, but what they got instead was somebody who was obsessed with Slovak separatism. The Gehlen Organization (now called the BND) terminated its associations with Ďurčanský in 1958, and he returned to Imperial America a year later. The CIA asked the State Department how he was allowed, to which it replied that despite his

“history of association with the Nazis, [and] his affiliation with the Slovakian separatist movement … there was nothing substantial on which to base a visa refusal.”

Ďurčanský presented hisself as the Anti‐Bolshevik Bloc of Nations’ chair, referring to the Third Reich’s dissatisfaction with his performance as evidence that he wasn’t a collaborator at all. It seems that from this point on his job consisted of peddling bullshite to everybody.

Despite some people speaking up, nobody did anything about him. The Immigration and Naturalization Service had no problem with Ďurčanský, but Jews and some Czechoslovaks did, which might have been a few reasons why he left for Munich in the early 1960s. (That was the State Department’s last chance to extradite him, and they blew it.)

Then, when some Czechoslovaks complained to Austrian authorities about him, they said that they’d ‘look into it’ (so they basically did nothing). Apparently, Canadian authorities didn’t give a toss either when he visited their country, then he returned to Munich safe and sound. He dropped dead in 1974.

Click here for more photographs.

[Notes]

Useful in this paper is the discussion on how Slovakian anticommunists sought the splitting of Czechoslovakia. For example:

Ďurčanský […] continued to work for the breakup of what was then called Czecho‐Slovakia. On March 13, 1939, Ďurčanský and Tiso had final discussions with Hitler and von Ribbentrop, and on the next day the Slovak Parliament declared independence.

Events that happened today (July 20):

1868: Miron Cristea, a monarchofascist, was released into the world.

1932: President Paul von Hindenburg in the Preußenschlag paved the way for the Third Reich by placing Prussia directly under the rule of the national government.

1940: Denmark, now a minor Axis power, left the League of Nations.

1944: Wehrmacht Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg tried and (sadly) failed to murder Adolf Schicklgruber.