As a clear measure of urban segregation preceding occupation, the new [Fascist] élite overtook the city’s core, with the local population removed and kept in Addis’ outer rings. This proto‐banlieu separated the city’s population with barriers in blue and green: that is, with tributaries of the Akaki River Basin, and with swaths of the region’s celebrated eucalyptus trees.

The move divided the market in two, creating one market for Ethiopians, and one for Italians. While the Governor’s Technical Office, alongside famous Rationalist architects such as Gio Ponti and Enrico Del Debbio used architecture to racially segregate vast zones of the city, the Merkato Ketema move is the only case of a site‐specific intervention to divide the population in terms of black and white.⁷

[…]

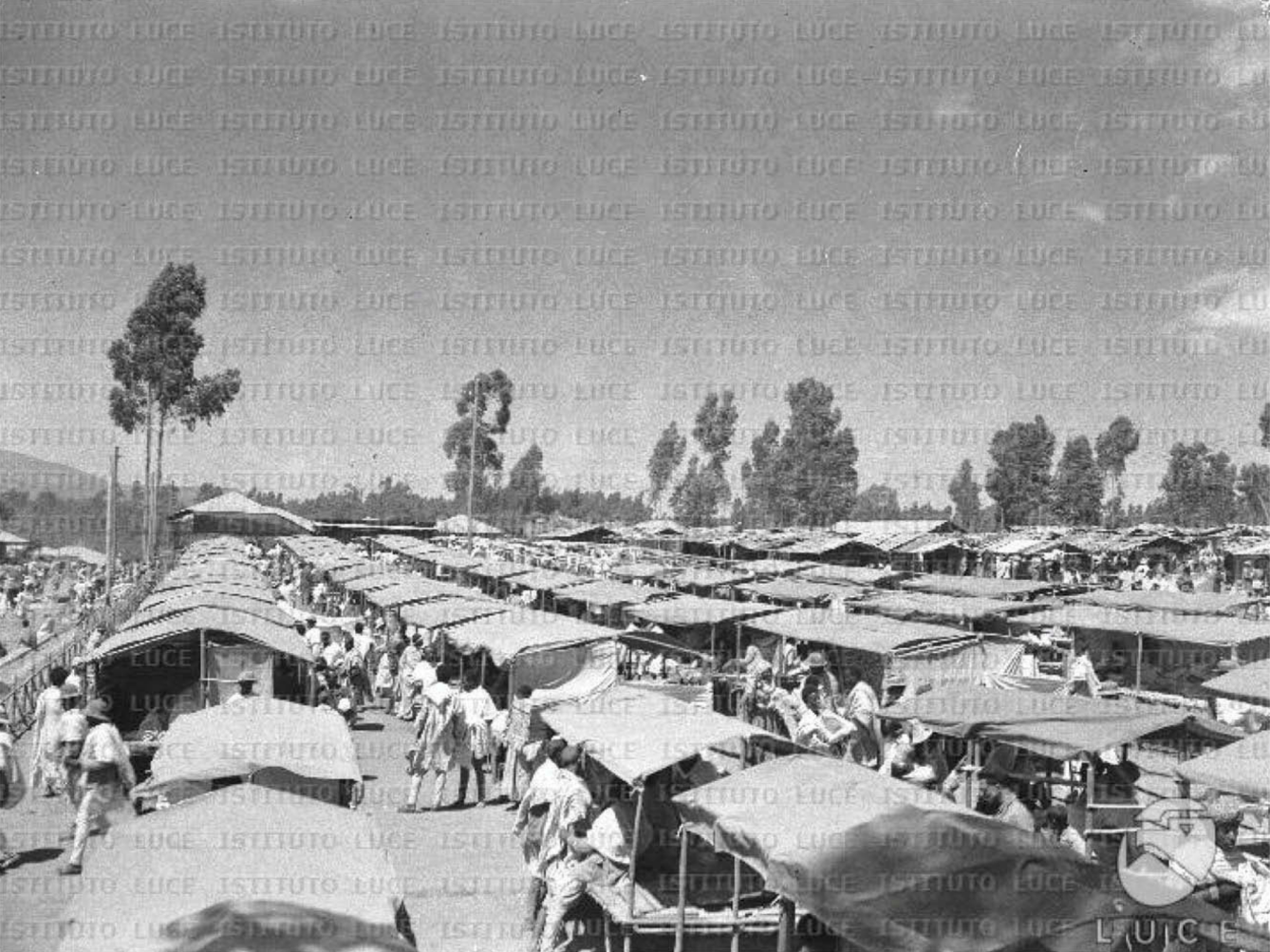

Fascist interventions to the Merkato Ketema in 1936–1938 show how the régime separated and intensified racial groups. Fascist modifications of the market layout show how the régime used architecture to attach qualitative cultural values to these newly constructed racial categories.

Flexible structure marked the original marketplace (Figure 3). Social agreement, rather than architectural structure, organized the market. What appeared chaotic to [Fascist] eyes bespoke years of careful negotiations between families of vendors.

[…]

How did Italians and Ethiopians actually use this space? At stake in these questions looms a larger issue, one that reveals the everyday workings of Italy’s racial politics the east African colonies: why markets figured so centrally to Fascist imperial ambitions in Ethiopia.

The […] League of Nations responded with economic sanctions against Italy, and this is where political events become salient for the marketplace newsreels. The Fascist régime heralded autarchy as a means to counter the financial squeeze. This turn of events explains L.U.C.E.’s heavy promotion east African markets through film in subsequent newsreels.

Pyramids of cactus fruit and overflowing sacks of teff grains portrayed ample foodstuffs, a bounty waiting to be seized. In a loop of tautological reasoning, the invasion that led to the sanctions could also alleviate their effects. Ethiopian markets could potentially counter‐balance hunger in domestic Italy.

(Emphasis added. Click here for more.)

Disturbingly, Fascism also had long‐term consequences for this marketplace:

Indeed, the Merkato Ketema neighbourhood is now known for its poor urban planning, put into place by the Consulta centrale per l’edilizia e l’urbanistica in 1936. Local shopkeepers and stallholders live in poor conditions in the densely populated residential areas on the edge of Merkato or in more salubrious accommodation in the Kolfe district just west of the market.

Traffic clogs the narrow roads, built for the occasional colonial functionary’s Fiat 509, not for the enormous crowds of today. Examining the city’s impact on family life, Abeje Berhanu identifies the specific urban planning issues that have led to social breakdown.

Chief among the problems cited is extreme density. It translates to a shortage of recreational facilities, like parks and playgrounds for children. It means that health and educational facilities are likewise rare.²³

[…]

Lack of hygienic facilities, the original problem of Fascist refurbishments to the Merkato, continues to plague the space. To restate the issue, the 1936 plan eliminated centralized control by the merchant heads. Previously, these commercial leaders made arrangements to maintain a clean, central bathroom in Addis’ urban agricultural markets.

Under the Fascist régime, a host of new functionaries stood as autonomous masters of each marketplace segment. There was no incentive to take control of communal market hygiene. It rapidly declined as a result of these interventions.

Participants in Berhanu’s study indicated that some families use plastic bags to dispose of urine and human excreta, as they do not have access to toilets, creating major health problems in the area. Attempts to build community toilets have not materialized because of lack of space, another legacy of the 1930s grid system.

Little wonder then, that Eduard Berlan describes the devolution of the Merkato Ketema neighbourhood as the ‘most living’ heritage of the [Fascist] occupation.