British awareness of Japanese colonial operations did not end after [the Axis’s] defeat in 1945. Indeed, the success of Britain’s recolonization of Singapore and Malaya relied heavily on advice from, and consultation with, [Axis] military and civilian administrators awaiting repatriation to Japan, Korea and Taiwan in Singapore and Malaya between late 1945 and the middle of 1947, by which time most had gone home.⁴⁶

Shinozaki Mamoru, who had helped set up at least three protection villages and had preached the virtues of Pan‐Asianism to the residents of the New Syonan protection village near Mersing, was a senior advisor to the British authorities after their return to Singapore.

British military lawyers and intelligence officials also debriefed more than 12,000 [Axis] officers, NCOs, enlisted men, kempeitai military police, and Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese gunzoku auxiliary military personnel stationed in Singapore and Malaya at the time of the surrender.

Conducted by British personnel hastily trained to speak Japanese at the School for Oriental and Asian Studies in London and by Japanese‐Britons and Japanese‐Australians, interrogations ranged widely across [the Empire of] Japan’s conduct, methods, and policies in Malaya and Singapore.⁴⁷ It should not be surprising then, to happen upon elements of Japanese seized hearts counterinsurgency in the subsoil of British counterinsurgency in Malaya.

(Emphasis added.)

Interestingly, this style of counterinsurgency in turn derives indirectly from U.S. colonialists.

In colonial Hokkaidō, the army and colonial authorities sought to contain and abolish the disorder posed by Ainu with forced relocation into new communities.

It may have been that relocations in Hokkaidō were inspired by what Japanese colonial authorities had learned or heard from American advisors. Men with both direct and indirect experience in management of Native Americans in the western United States played significant rôles in the early colonization of Hokkaidō.

In 1870, Kaitakushi (Hokkaidō Colonization Commission) hired Horace Capron to advise on commercialization and eventual mechanization of agriculture in Hokkaidō. His résumé included dispossession and relocation of Native Americans from their lands in Texas after it was wrested from Mexico in the Mexican American War of 1846–1848 and opened up to large‐scale settlement.

To work with him in Hokkaidō, Capron hired men with similar credentials: surveyors, geologists, and agronomists with experience in management of lands taken from indigenous Americans and in removal of native peoples to make way for railroads, mines, and farms.⁸

Though the Ainu posed little real threat of insurgency in Hokkaidō, they did not surrender to Japanese rule passively: Ainu did not rebel but they were often reluctant.⁹ The Japanese state set about using modernity to vitiate Ainu difference and the threat it posed to modern order.

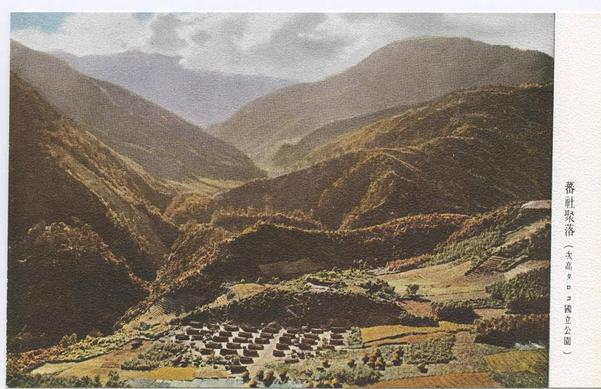

By the end of the 1880s, many Ainu had been forced into new communities on lands often far from ancestral territories. Here, they were subject to the suasions of the modern state while their lands were released for exploitation and profit taking.

What had been gleaned from American advisors about managing reluctance and avoidance and the potential threat of conquered populations now intersected in Hokkaidō with Japanese ideas about a modern national subject and Japanese anxieties about the security of the state. The key imperial Japanese counterinsurgency principles of clearance, hold, protect, and formation of loyal or at least submissive hearts and minds first emerged here.