- cross-posted to:

- history@hexbear.net

- cross-posted to:

- history@hexbear.net

(Mirror.)

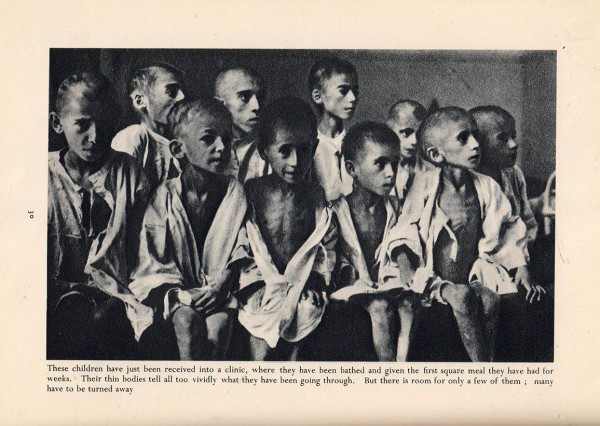

It should be noted that the primary factor in the excessive mortality of the Greek population during the [Axis] occupation was starvation. Indeed, as Valaoras pointed out, starvation was the underlying cause of death for several thousands of Athenians during that time. We can also reasonably speculate that deaths ostensibly due to tuberculosis, for example, were expedited by the hunger famine of the period under review.

Interestingly, the [Wehrmacht] imposed food rations based on racist basis with Germans receiving biggest food rations in [Axis] occupied territories of Greece, with little spared for [the] Greek population. In fact, the Greek population in Athens during the winter 1941–1942 received only 53,15 gr of bread.

On the contrary the members of the German community in Athens received 1771,85 gr of bread per week, and also 354,37 gr of meat, 88, 59 gr butter, 354,37 gr olive oil, 177,18 gr rise or legumes, 177,18 gr pasta, 177,18 gr sugar, 17,71 gr coffee, 8,85 gr tea and 3,54 gr egg [3,14,15].

This practice was in line with the [Fascist] policy in the occupied Poland. Both Polish and Jewish population was considered by [Fascist] authorities to be “sub‐human” (Untermensch) and as such targeted for extermination. Under [the Axis’s] plans, deliberate starvation of [those who] were considered “sub‐humans” was considered. In particular, by 1941, the official ration provided 2613 calories daily for Germans in Poland, 699 calories for Poles, and 184 calories for Jews in the Warsaw ghetto [16].

[…]

In conclusion, we found that the Axis […] occupation of Greece has had considerable health effects on infectious diseases and hemorrhagic stroke mortality. It should be stressed that deaths ostensibly due to infectious diseases (e.g. tuberculosis or malaria), were expedited by the hunger famine of the period under investigation.

With regard to the elevated mortality due to hemorrhagic stroke, we believe that the stressful events of occupation and famine have triggered increased psychosocial stress which in turn may have increased the risk of hemorrhagic stroke mortality during the period of Axis […] occupation of Greece.

Quoting Mark Mazower’s Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44, page 41:

The Red Cross, which commissioned its own study, estimated that about 250,000 people had died directly or indirectly as a result of the famine between 1941 and 1943. Taking into account the shortfall in the number of births over the same period, it reckoned that the total population of Greece was at least 300,000 less by the end of the war than it would otherwise have been, as a result of food scarcity.⁶⁵

(Emphasis added. Click here if you have time to read more.)

The Axis resorted to both formal and informal means to exploit Greece for resources to feed into the Axis’s militaries. Page 23:

The [Axis’s] troops appeared undernourished, tired and even ‘half-starved’ when they first arrived. Though the occupation itself proceeded with little violence, the soldiers took food and requisitioned what they liked. ‘The Germans have been living off the country,’ wrote an informant who left in July, ‘They brought no food for the troops with them and no soldiers’ messes; the troops simply ate in restaurants. The troops were not in camps, to avoid bombing, but in private houses. Many were thoroughly looted.’

[Axis] soldiers reportedly stopped passers-by in Omonia Square to demand watches and jewellery. A Greek harbour official returned to his office a few weeks after the occupation had begun to find that ‘there is nothing left of my old office. Everything which could be of use to the German authorities, desks, chairs, safe etc. has been taken off by them. The rest has been destroyed or used as firewood.’¹⁷

Page 24:

However, alongside plundering by individual soldiers, supply officers were requisitioning much larger quantities of goods: 25,000 oranges, 4,500 lemons and 100,00 cigarettes were shipped off Chios within three weeks of occupation.

The steamer Pierre Luigi, which left Piraeus in June, carried a typical cargo — hundreds of bales of cotton goods, jute, and sole leather which had been seized from Greek warehouses to be shipped north on behalf of the Wehrmacht High Command. Army officers also seized available stocks of currants, figs, rice and olive oil.²¹ James Schafer, an American oil executive working in Greece, summed it up: ‘The Germans are looting for all they are worth, both openly and by forcing the Greeks to sell for worthless paper marks, issued locally.’²²

Pages 27:

The economic policies which the Axis authorities followed in the first weeks of the occupation threw the prewar collection system into disarray. [The Axis] set up road-blocks, checked warehouses and seized crops for the use of their troops.

Such actions, together with the rumours [that] they generated, made farmers hesitate to bring their crops to market, or even to declare the size of harvest they anticipated. At the same time, the requisitioning of pack-animals increased the cost of transporting foodstuffs from farming areas to the towns where they were needed.³²

Prices rose steadily, fuelled by the money printed to cover the demands of the occupation authorities. Inflation led producers and retailers to withdraw their goods from the market, and hoarding became widespread.

Ignoring the official purchase price for wheat set by the authorities in June, farmers sold at double the price or more to the military supply officers and dealers who were touring the countryside. They paid little attention to decrees which ordered them to deliver fixed amounts to the state marketing agency and penalised black market sales with death.

The Tsolakoglu government tried sending demobilised army officers out to help collect produce. But these officers often sided with the farmers as they did not believe that the crops would go to feed their fellow-countrymen and suspected that they would be shipped to North Africa for Axis troops instead: sabotaging the government’s efforts to collect grain thus became an act of resistance.

Shepherds refused to hand over their milk to state authorities at what they regarded as inadequate prices. A provincial daily reported in disgust: ‘The [shepherds] regard the milk as theirs to be distributed as they wish. In other words, the shepherds are completely indifferent to any state decree.’³³

If you are a free market purist, I have no doubt that you are gullible enough to believe that merely seizing and artificially cheapening food to feed an anticommunist army (never mind the lower classes) is a form of ‘socialism’. Add this to your modus operandi of ignoring the freer markets that contributed to the Axis war machine, you’ll be winning all those Internet arguments in no time.

Pages 30–31:

In July Altenburg did succeed in attracting Hitler’s attention to the problem. But barely a month into the invasion of the Soviet Union, his supreme gamble, the Führer did not pay much attention to what he must have regarded as a rather marginal matter. He issued vague orders that help should be provided if possible, at least in the zones still occupied by [Wehrmacht] troops.

In Berlin, however, the Ministry of Food and Agriculture was against giving any assistance to Greece at all. The Foreign Ministry tried arguing that the Italians had originally agreed to take responsibility for provisioning Greece. But as [Fascist] Italy had no surplus of its own and was in fact increasingly dependent on German food imports, this stance virtually condemned Greece to starvation.⁴³

As the summer ended [Axis] diplomats did draw up a schedule for the monthly provisioning of Greece until the end of June 1942. Once again, however, no grain was to be made available for export from the Reich. The [Third Reich] simply agreed to transport 10,000 tons of grain from other occupied regions, so long as [Fascist Italy] would ship over the same amount.

Another 40,000 tons were to be delivered during the last three months of 1941, 15,000 tons in January and February. This grain too was to come, not from the Reich itself, but from Greece’s neighbours. Bulgaria was earmarked as the most likely source since she was not at that time supplying [the Third Reich].

Yet Bulgaria was still an independent state and not one traditionally friendly towards Greece, some of whose northern territories she was currently despoiling. Her government wasted little time in making it quite dear to Berlin that her own food requirements left none over for Greece.

By October, Berlin had evidently lost interest in the Greek food problem. So far as officials in the Ministry of Food were concerned, no grain could be shipped out to Greece without jeopardising [the Third Reich’s] own supply. Ribbentrop at the Foreign Ministry declared that there were no pressing foreign policy reasons to worry about Greece at the Reich’s expense.

And from Field Marshal Göring’s Four-Year Plan Ministry came the coup de grâce: if food supplies were to be sent anywhere in occupied Europe, Belgium, Holland and Norway should receive priority over Greece. In the [Axis] pecking order she was near the bottom of the list.⁴⁴

Meanwhile the Armed Forces Supreme Command announced that the rail line from Salonika to Athens was badly damaged. This meant that trains were subject to long delays and could not be used to carry grain supplies south.⁴⁵

Charting the amount of food the Axis powers actually sent in this period into Greece underlines Berlin’s indifference to what was happening. In the period from 15 August to 30 September [Fascist Italy] sent in 93,000 quintals of grain, most of it to the Ionian islands, Epiros and the Cyclades. This total was not much short of the 100,000 quintals [that] they had pledged to send.

The [Third Reich], however, sent only 50,170 quintals before bluntly informing Rome that ‘for the future the Italian government must take the responsibility for provisioning Greece, since Greece lies in Italy’s sphere of influence’.⁴⁶

Further reading: Early‐Life Famine Exposure and Later‐Life Outcomes: Evidence from Survivors of the Greek Famine (mirror).

Famine and Death in Occupied Greece, 1941–1944

Click here for other events that happened today (February 22).

1904: Franz Kutschera, major general in an Axis police force, was sadly born.

1932: Joseph Goebbels announced on Adolf Schicklgruber’s behalf that Schicklgruber would run for the office of the President of Germany, challenging incumbent Paul von Hindenburg. The Imperialists also lost one bomber over Shanghai.

1933: Hermann Göring established an auxiliary police force in Prussia, staffed mostly with members of the SA organization, and Berlin made its initial plans for a detention camp in Oranienburg.

1940: Georg von Küchler ordered his subordinates to stop all forms of criticism toward the Reich’s racial policies.

1941: The Axis deported 430 Netherlandish Jews from Amsterdam to Auschwitz as reprisal for the murder of a Netherlandish Fascist.

1943: The Kingdom of Bulgaria agreed to Berlin’s demand to deport 11,000 Jews from twenty‐three communities in Thrace and Macedonia, occupied areas of Yugoslavia and Greece. It sent them to Treblinka where many of them subsequently died.