Excerpts:

Fifty-nine years ago, on Sept. 11, 1964, Korea sent 140 soldiers belonging to the medical corps to Vietnam as part of the war effort. Over the nine years that followed, South Korea would end up sending a total of 346,393 troops to fight in Vietnam in its Blue Dragon, Fierce Tiger, and White Horse divisions.

In 1999, Hankyoreh 21 broke the story that South Korean troops had massacred civilians in Vietnam with in-depth reporting. More than 20 years later, in February of this year, a South Korean court ruled that the country bears a legal liability to those victimized by these massacres. However, the South Korean government still insists that no such slaughter occurred.

This is the first time that Bình Thanh is being named in the history of Korea’s involvement in the Vietnam War that began in 1964. Bình Thanh is not mentioned in the official “War History of ROK Forces to Vietnam” published by Korea’s Department of Defense in 1979.

57 years ago, as a 10-year-old girl, Tống Thị Kim Loan said she picked peppers in the fields with her grandfather, Tống Mai. […] the villagers had heard that South Korean soldiers couldn’t get enough of them. The young girl and her grandfather packed the peppers in small bags and took them to the Korean soldiers at the Go Cot base.

When Tống Thị Kim Loan’s grandfather, Tống Mai, arrived at a South Korean military post, he had Vietnamese peppers and a letter in his hand. He was accompanied by Cao Phó and Mai Cắt, who lived in his same village. The three of them represented the village and faced the South Koreans for the first time. All three were born in the 1890s and were over 70 years old at the time. Their letter to the South Koreans was written in Chinese characters. Having learned to read and write Chinese characters from a young age, they assumed that the Koreans would be able to read it as well.

The South Korean soldiers based in Bình Thanh did not have interpreters. The letter contained a heartfelt plea from the village elders: “The villagers are all innocent civilians. Please do not harm them.”

A young Tống Thị Kim Loan was holding her grandfather’s hand when he presented the Korean soldiers with the letter and his gift of peppers.

A month after Tống Thị Kim Loan and her grandfather offered the chilis to the soldiers, the South Korean soldiers paid a visit to Tống Thị Kim Loan’s neighborhood. Instead of gifts, they brought guns.

CW: Details about the massacre

The South Korean soldiers visited her house early in the morning, before breakfast, at around 6 or 7 am, she said. They forced the family outside. She stepped outside with her mother, 30-year-old Mai Thị Én, and younger brothers, 7-year-old Tống Phuong and 6-year-old Tống Hoang. Six members of Von Ke’s family, who lived in the same neighborhood, were also dragged out into the street, making for 10 people in total.

At first, the soldiers handed out canned food, most likely C-rations. Some of them started to set up a submachine gun under a big tree. After some time had passed, there was a huge bang, as if something had exploded. Then, there was smoke everywhere. It was impossible to see anything. The soldiers had set off a smoke bomb.

The thunder of the gun rattling off its bullets shook the ground, and the sound was ear-splitting. Tống Thị Kim Loan grabbed her mother and hid behind her. People fell to the ground as they screamed, and Tống Thị Kim Loan happened to fall underneath everyone else. The gunfire stopped. So did the groans of agony.

Tống Thị Kim Loan seized her wits and got up. She wondered if the soldiers had set off the smoke bombs because they were afraid to see what they were doing, mowing down people with their guns. The soldiers left the village to return to their base without checking the bodies, which was a stroke of luck in Tống Thị Kim Loan’s favor. She suffered only a small burn on her stomach. She can still remember the chilling sensation of the bullet grazing her belly.

Tống Thị Kim Loan’s father, who had fled from the scene, returned at night to collect the bodies with the village elders. A banana tree was planted at the grave of the girl’s mother. Her mother had been in full term. Planting a banana tree to celebrate a pregnancy was a village tradition. When it was time to give birth, villagers celebrated the birth of a new life by eating bananas from the tree. However, her mother would never be able to commemorate anything any longer.

“All the village elders who visited the soldiers with the chilis died,” said Le Van Hien, 76. Presenting a list he wrote on the computer, Le Van Hien pointed at the three names at the top of the list: Tống Mai, Cao Phó and Mai Cắt. These were the names of the village elders who had visited the South Korean soldiers with the bag of chili peppers and a letter written in Chinese characters.

Le Van Hien has been recording the history of how the people of Bình Thanh fought against outside forces. His records from 1930 to 1975 have already been published into a book, which contains stories of people who died at the hands of South Korean soldiers.

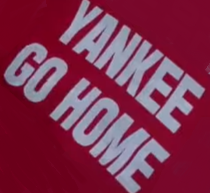

Following the end of the Vietnam War in April 1975, memorial monuments were erected in villages where residents were lost at the hands of South Korean soldiers. Monuments of “hate” were built in places such as Bình Hòa and Phú Yên. In some regions, monuments were erected 50 years after the war.

“I will propose the erection of a monument of hate rather than a memorial monument,” said Le Van Hien, explaining that this is because all the victims were helpless elders, women and children. Referencing the Vietnamese government’s slogan of overcoming the past and moving toward the future, Le Van Hien wordlessly shook his head.

“Still, I can’t help but hate. Incidents like this should be abhorred forever,” he said.