Do the middle ages have minimal relevance to modern history? Contrary to first impressions, maybe not. Research indicates that anti‐Jewish sentiment from the mediaeval period never fully faded away, and only made the NSDAP’s job of attracting support easier:

Churches from Cologne to Brandenburg displayed (and many still display) a Judensau, the image of a female pig in intimate contact with several Jews shown in demeaning poses. The same type of sculpture can also be found in Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, France, and the Low Countries.

[…]

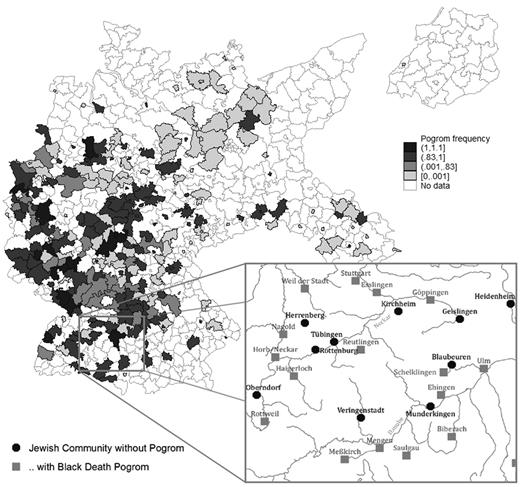

Before turning to the regression results, we examine differences in various twentieth-century outcome variables between cities that did and did not experience Black Death pogroms. As Table IV shows, pogroms in the 1920s were substantially more frequent in towns with a history of medieval anti-Semitism.

Similarly, vote shares for the Nazi party (NSDAP) in 1928 and for the anti-Semitic DVFP in 1924 (when the Nazi Party was banned) were more than a percentage point higher—which is substantial, given that the average vote shares were (respectively) 3.6% and 8%.

Our three proxies for anti-Semitism in the 1930s also show marked differences for towns with Black Death pogroms: the proportion of Jewish population deported is more than 10% higher, letters to the editor of Der Stürmer were about 30% more frequent, and the probability that local synagogues were damaged or destroyed during the Reichskristallnacht of 1938 is more than 10% higher.

Very few things change as slow as human habits, sadly