Evidently, there was an enormous difference between what was happening in Republican Spain and what was actually known about it, especially in a context of scarce information and inordinate political manipulation in Italy.²⁴ Many legionnaires based their decision to go to fight in Spain on distorted, propagandistic information. Indeed, stereotypes and biased news reports regarding anti‐clericalism, killings of priests and sacrophobic violence carried immense qualitative weight in motivating the first wave of enlistments.

Echoes of religious persecution in revolutionary Spain had helped to magnify what Giulio Castelli described — in 1951’s La Chiesa e il fascismo (a somewhat conditioned interpretation written six years after the end of fascism) — as the ‘generous, heroic participation of Italian volunteers’ in the fight ‘against barbarism and atrocities of international atheistic communism in all its Bolshevik extremism and terrorism’.

According to Dario Ferri (a pseudonym given by the person who interviewed him, who did not have permission to reveal the individual’s real identity), the volunteers went into combat as the ‘new legionnaires of Christ’.²⁵ ‘We volunteers’, they would say, ‘are the true crusaders of the fascist idea that will triumph with our infallible victory over all Spain, imposing on our enemies the human and divine truth it brings with it’. These fascist Italians were on a sacred crusade ‘for the homeland and for Christ’ against atheistic terrorism and Bolshevik barbarism.²⁶

Edgardo Sogno’s perspectives on the war were later collected in a small volume Due fronti, where he recalls his decision in 1938, at the age of 22, to fight for the victory of the ‘national’ Spain and ‘eject the communists from within Europe’.²⁷ The violent ‘revolution’ of the war facilitated a clash between ‘Bolshevik materialism and Roman Catholic spiritualism’;²⁸ only a poor Italian or a bad fascist would not have followed the ‘so, so many Italians who spontaneously go there, where the Ideal [sic] calls them’.²⁹

The section of the book La Grande Proletaria attributed to Arconovaldo Bonaccorsi (‘Count Rossi’) is clearly plagiarized from the Spanish falangist Agustín de Foxá, and as such repeats many classic images of Red terror and odious characterizations of the enemy.

Nevertheless, its rhetoric provides some enlightening insights into Italian fascist antirevolutionary perceptions. ‘Count Rossi’ depicts a Spain of ‘azano [sic, referring to Azaña] and quirosa’ [sic, referring to Casares Quiroga]’ which has been turned into ‘a province of the Socialist Homeland’, a ‘branch office’ of the Soviet Union in Europe.

This ‘forward base’ is full of loveless women with flaccid bellies and rickety, hunchbacked men, alcoholics reeking of blood, people who have never set foot in a museum and satanic beings with ferocious smiles, driven by diabolical obsession.³⁰

Mussolini himself wrote in the Proceedings of the Grand Council of Fascism that in Spain for the first time — and perhaps the last — the Blackshirts had faced Bolshevik forces on the international stage in the first confrontation between two revolutions: the reactionary one of the nineteenth‐century, and the twentieth‐century fascist one.³¹

Later on, another book in honour of the legionnaires described them as ‘Volunteers for Civilization, defenders of human and divine law, soldiers of the new Europe’ who would be endowed with the ‘supreme and eternal principle’ of faith, progress, peace, concord, exaltation of life, for honouring women and defending children, for opposing the ‘spasmodic hordes’, the ‘barbarians’, the ‘unleashed human beasts’ and their obsession with death, massacre and savagery.³²

This narrative would permeate all Italian fascist cultural, literary, scientific and technical fields just as European Red Terror literature had. General Sandro Piazzoni recalled how the national anthem played as the volunteers were shipped off to Spain to face ‘sacrifice and death for the triumph of fascism over Bolshevism and of social order over crazed criminal barbarism’.³³

Here we see the power of atrocity stories, a strangely chivalrous self‐image, and a lack of self‐awareness, as these antisocialists not only failed to understand Fascism as reactionary but also forgot about the atrocities that they committed in Libya, Corfu, and Ethiopia, and some of which they were about to repeat in Spain, too. The similarities between Fascist antisocialism and generic antisocialism are also hard to overlook.

However, these antisocialists needed more than just chivalrous duties and solidarity with a fellow Latin civilisation to risk their necks out in the wild. They needed a reason to believe that this was in their best self‐interest, specifically that a communist victory in Spain would eventually mean the triumph of communism in Italy and the rest of Europe: an assertion that bears a resemblance (almost strikingly so) to the ‘domino theory’ that later antisocialists used to justify the war on Vietnam.

This offensive and defensive anti‐communism would protect fascist identity: volunteers would not be shedding their blood under a foreign flag, but ‘for the salvation of a common civilization’ under the fascist flag, as only the Duce understood. ‘Anti‐fascists’ included all the enemy forces, and fascism was what ‘democratic Bolshevism’ strove to bury. To some, ‘so much Italian blood sacrificed’ for the cause was crucial for Spain but not always considered beneficial for Italy.

However, this was not mere generosity and sacrifice. These aristocrats, imbued with warrior courage, would fight to fulfil the ‘political and spiritual objectives of the Italian Nation [sic]’.³⁴ ‘It was right’, said Italian National Volunteer Commander Eugenio Coselschi in the commemorative volume Legionari di Roma, that in ‘Mediterranean Spain one fought and won in the name of Rome’. To defend the Mediterranean was to defend ‘the tradition and unity of the entire European continent’ and to stop ‘Soviet leprosy’, that ‘voracious Empire’ from corroding its shores.³⁵

Click here for a review of the Italian Fascists’ atrocities in Spain.

Naturally, somebody spread rumours about us committing cruelties reminiscent of The 120 Days of Sodom:

Sandri conceded that testimonies of the ‘Red terror’ […] were appalling. However, he also noted that they were somewhat incongruous, given that retreating forces have little time for such excesses.

This is inevitably going to remind readers of the many dubious October 7th atrocities that Zionism’s propagandists have attributed to Hamas, most of which were improbable given the nature of the similarly time‐sensitive operation (among other reasons). Moreover, not only did the Fascists commit similar atrocities, but they are much better substantiated:

The camp authorities — as the director of the San Juan de Mozarrifar concentration camp complained — imposed punishments which contravened the code of military justice, such as tying prisoners by their hands and feet to trees or lampposts ‘for several days’. Frecce Nere officials from Dario Ferri’s unit summarily executed four Civil Guards who had shot at them from the Girona castle as they occupied the city.⁷⁰

[…]

[Fascist] forces bombed Lleida on 2 November 1937 (wounding many civilians, including schoolchildren), Barbastro on 4 November and other parts of Aragon such as Bujaraloz, Caspe and Alcañiz, ending an intense year of aerial destruction. However, this destruction was but a prelude to the campaign of 1938, the year in which the Aviazione would carry out its highest number of attacks. These bombing raids, which increasingly targeted non‐combatants, formed part of a mission to terrorize the Red rearguard and especially urban centres.

Almost all the larger cities along the Catalan and Valencian coast were bombed regularly during these months by both the Italian forces and the German Condor legion. These included Tarragona and Reus (more than fifteen times), Gavá, Badalona and Mataró. From its Logroño base, the Aviazione devoted itself fully to supporting the territorial occupation of Aragon (Alcañiz, Sariñena, Fraga, Monzón) and inland areas of Catalonia.

However, few aerial raids had such lasting repercussions as those carried out on the Republican capital of Barcelona. The bombardment that took place on New Year’s Day was ordered by Mussolini and carried out by General Valle, though Ciano had not been notified beforehand. General Valle wrote that this aerial terror campaign had two objectives: to demonstrate clearly that [Fascist] planes could carry a tonne of bombs for over a thousand kilometres and to ‘give the Reds in Barcelona a New Year’s welcome that will cause them to meditate on the Teruel defeat.’

In complete radio silence and with 850 kilograms of bombs loaded into his S.79, bombs were dropped from 3,000 metres (and from 5,000 meters when reflectors were lit), catching the defenders by surprise: the gunners must have been out ‘celebrating New Year’s Eve’.

As an epilogue to this macabre report, General Valle thanked the Duce for the ‘high honour’ of having been chosen for this mission and having demonstrated ‘with legitimate pride’ that in the nineteen years that had passed since his last bombing raid, his physical prowess and military experience had remained, as always, in the hands of […] fascist fortune.⁷³

This terror campaign on Barcelona reached its greatest intensity with the attacks of 30 January and especially 16–18 March. [Fascist] planes bombed the port and city centre for up to eight days in January, destroying aerial defence shelters such as the San Felipe Neri church.

Ciano confessed in his diaries that the report which described the 30 January bombing raid was the most horrifying one that he had ever read, despite the fact that the attack had been conducted by only nine S.79 planes and had lasted only one and a half minutes: ‘pulverized buildings, interrupted traffic, panic that turned into madness, with 500 dead and 1,500 injured. A good lesson for the future’, as it revealed the ineffectiveness of anti‐aircraft defences and shelters. Thus, ‘the only means of salvation against aerial attacks is to abandon the cities’.⁷⁴

On 16 March, Mussolini directly ordered the Aviazione to ‘initiate from this evening’ a ‘violent action on Barcelona’ in the form of ‘rhythmic hammering’ with thirteen flights organized in such a way that the city centre would experience the bombs and sirens from beginning to end.⁷⁵

This supplies empirical evidence of the degree of autonomy that the Aviazione Legionaria exercised with respect to Francoist command. Scholars consider the [Fascist] bombing of Barcelona to be a series of deliberate attacks on civilian populations on the home front. In 1938, there were also attacks on munitions and weapons factories, ports, airports and petrol deposits, all of which were located outside the city centre.

The Aviazione Legionaria chain of command did not even go through the CTV [Corpo Truppe Volontarie] command, but depended directly on the government in Rome. The bombings of Barcelona, Alcañiz, Granollers, Alicante, and later Sitges or Torrevieja were indiscriminate attacks on military and civilian targets; their random nature was intended to terrorize non‐combatants and decrease resistance. This conclusion has been corroborated by others. […] Smyth‐Piggott and Leneune concluded that the bombings were deliberate attacks on civilian areas.

I feel like this is so obvious that I need not spell it out, but in case somebody reads this several years later: this sounds identical to Zionism’s aerial terror bombings of Gaza.

Fascist Italy’s contribution to the Spanish Civil War was so important that it is doubtful that anticommunism would have triumphed otherwise:

In late September 1937, [Fascist Italy] had 376 airplanes in Spain, compared with forty‐two Spanish planes. […] The final count of 78,474 troops (45,000 regular army, 29,000 MVSN fascist militia (Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale)) may not appear numerically significant at first glance. However, if we understand [Fascist] Italian involvement as an intervention in support of an allied faction in a domestic war, we see that [the Regio Esercito] represented a quarter of the total forces used in conquering the fascist empire, and almost double the number of soldiers who fought in the International Brigades.

Mussolini achieved the true internationalization of the Spanish Civil War, deploying the largest contingent from one single foreign country to Spain. His troops accounted for approximately one tenth of the estimated overall total membership of Franco’s Army, and he spent the equivalent of an entire annual budget for the armed forces — some 8.5 billion liras — in Spain.⁷⁷

[…]

[Fascist Italy was] crucial to the success of the Rebel army in occupying Malaga, Bermeo and Santander, in breaking through and stabilizing the Aragon front, in the occupation of Barcelona and Girona and in concluding the Levantine campaign.

(Emphasis added in all cases.)

Hence, il Duce could brag on January 26, 1939 that

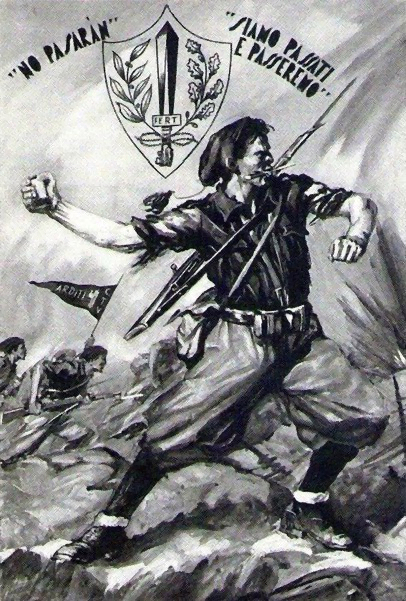

The shout of your legitimate exultation merges with the shout rising from all the cities of Spain now wholly free from the Reds’ infamy, and with the shout of the anti‐Bolsheviks from all over the world. The bright victory of Barcelona is another chapter in the history of the new Europe we are creating. Franco’s magnificent troops and our intrepid legionnaires did not defeat only Negrín’s government. Many others among our enemies are biting the dust right now. The Reds’ watchword was ‘No pasarán’, but we passed and, I am telling you, we will pass.¹³⁰

Well, I hate to say it, but with the loss of the Republic in 1939 it does look like he had a point there (for once)… then again, given the thousands of holdouts in the Spanish State, the Axis’s defeat in 1945, how the institution of Iberian parafascism ended with a bang in the mid‐1970s, and the decline of Imperial America as we speak… I’ll let you decide who is getting the last laugh.

Click here for events that happened today (September 24).

1884: Hugo Schmeisser, Axis arms designer (who, I’ve read, frequently influenced Schicklgruber and Göring’s decisions), started existing.

1922: Ettore Bastianini, Axis aviator, was born.

1935: The Third Reich’s Minister for Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, appointed a Reich Church committee to supervise the local committees of dissident Evangelical Churches.

1936: The Fascists commissioned U‐23 into service.

1938: As Neville Chamberlain departed Bad Godesberg to return to London, Berlin promised him that the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia would be the last German territorial demand in Europe. Paris rejected Berlin’s latest demands; the French military partially mobilized in preparation for war.

1939: Limited food rationing began in the Third Reich, and Einsatzgruppen exterminated eight hundred members of the Polish intelligentsia at Bydgoszcz. As well, the Fascist submarine U‐4 (Oberleutnant zur See Harro von Klot‐Heydenfeldt) stopped the 1,510‐ton Swedish merchant steamer Gurtrud Bratt southeast of Jomfruland. As the ship was registered in a neutral country, the Fascists demanded to see the ship’s papers. The Swedish ship was loaded with wood pulp, paper and cellulose and bound for Bristol. Regarding this cargo as contraband, the Fascists ordered the master of the Gurtrud Bratt, E. K. Jönssen, to get his crew into the lifeboats as he was going to sink his ship. As there were no more scuttling charges on board, the submarine sunk her with a torpedo. According to the survivors the Fascists had promised to tow the two lifeboats towards the nearby Norwegian coast but apparently the submarine left without helping them after sighting a flightcraft.

1940: At 0830 and then again at 1115 hours, a couple hundred Fascist bombers, escorted by twice as many fighters, took off to assault targets in Kent in southern England; Portsmouth, Southampton, and the nearby Spitfire fighter factory at Woolston were among the targets. Meanwhile, as the Prime Ministry announced plans to expand evacuation, 444,000 children had already evacuated from the London area. The arrival of Fascist bombers on this night marked the eighteenth consecutive night in which London had been bombed; Liverpool, Dundee, and other cities and towns were also bombed. Meanwhile, the Imperialists occupied Lang Son, Indochina.

1941: The Armeegruppe Sud started its offensive from southern Ukraine towards Crimea, and Einsatzgruppe C set up its headquarters in Kiev. As well, Axis submarines U‐107 and U‐67 attacked Allied convoy SL‐87 and sank four ships west of Madeira island, slaughtering sixteen folk, but 197 survived.

1942: The Armeegruppe A launched an assault against Tuapse on the Black Sea, and the Third Reich’s 94th Infantry Division and 24th Panzer Division effectively wiped out all Soviet units in the southern pocket in Stalingrad. To make matters worse, Axis bombers attacked Hastings in England, leaving nineteen dead and seventeen seriously injured. The Axis also assaulted Seaford in southeastern England. Axis troops landed on Maiana, Gilbert Islands, and Berlin sacked General Franz Halder as Chief of Staff, replacing him with General Kurt Zeitzler.

Axis submarine U‐432 sank Allied ship Penmar east of southern Greenland at 0144 hours, leaving two dead but fifty‐nine alive. In the same general area, U‐617 sank Belgian ship Roumanie at 0158 hours, massacring forty‐two people and leaving only one human alive. At 0924 hours, U‐175 sank Allied ship West Chetac north of Georgetown, Guyana; thirty‐one died while nineteen did not. At 1825 hours, U‐512 sank Allied merchant ship Antinous (under two by British rescue tug HMS Zwatre Zee) also north of Guyana. At 1910 hours, U‐619 sank Allied ship John Winthrop southeast of Greenland, slaughtering all fifty‐two aboard.

1943: Axis submarine U‐711 shelled the Soviet wireless telegraph station at Blagopoluchiya in northern Russia.

1944: Axis submarine U‐739 sunk the Soviet minesweeper T.120 (formerly the USS Assail) in the Kara Sea in the Arctic Circle. Additionally, the Axis sealed off the U.S. Third Army’s bridgeheads across the Moselle River, south of Aachen.

1945: Hans Geiger, Axis physicist, expired.

1978: Freiherr Hasso Eccard von Manteuffel, Axis general who was born into a Prussian noble family and eventually lectured at the United States Military Academy at West Point, mustered up the decency to finally drop dead.